Antonio Rosas1, Antonio García-Tabernero1,2, Darío Fidalgo1, Maximilian Fero3 and Juan Ignacio Morales4,5

1Group of Paleoanthropology, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, Madrid, Spain

2Area de Antropología Física, Facultad de C. Biológicas y Ambientales, Universidad de León. Campus Vegazana s/n, 24071, León, Spain.

3Universidad Nacional de Guinea Ecuatorial (UNGE), Equatorial Guinea

4 Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social (IPHES-CERCA), Zona Educacional 4, Campus Sescelades URV (Edifici W3), 43007 Tarragona, Spain.

5Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Departament d’Història i Història de l’Art, Avinguda de Catalunya 35, 43002 Tarragona, Spain.

Figure 21. Situation maps, adapted from Rosas et al. (2025). A) Map of Africa showing the location of Equatorial Guinea, highlighted with a red ellipse, on the west-central coast of the continent. B) Continental part of Equatorial Guinea (Río Muni) with the surveyed area framed in red. C) Enlargement of that area showing the Río Campo region in detail with the surveyed points (pink) along with those where lithic industry was found (yellow, labelled with point number). The Ntem River (formerly Campo), bordering Cameroon, can be seen to the north.

The study of human evolution within the tropical rainforest ecosystems of Central and West Africa presents a crucial challenge for understanding the biological and cultural development of Homo sapiens (Ben Arous et al., 2025). These environments provide significant insights into early human adaptations and technological strategies, but the lack of comprehensive archaeological and chronological sequences has made it difficult to place them within the broader evolutionary framework. A recent study presents findings from research conducted in the Río Campo region of Equatorial Guinea (Figure 21), focusing on Pleistocene occupations and the persistence of Middle Stone Age (MSA) technologies in this understudied area (Rosas et al., 2025).

Tropical rainforests have long been considered marginal environments for early human habitation due to their challenging conditions, including high humidity, dense vegetation, and resource variability. However, the discovery of extensive MSA lithic assemblages in the Río Campo region challenges this assumption and provides evidence that early human groups successfully occupied and exploited these landscapes. In particular, Campo 11 (Figure 22), situated a few kilometers from Río Campo town (2◦19′06.68″ N, 9◦47′05.00″ E), stood out for its extensive, high-quality material exposure and an abundance of lithic artefacts. A horizon rich in lithic remains and charcoal fragments suitable for radiocarbon dating was detected. This study aims to shed light on the technological, subsistence, and settlement strategies employed by ancient humans at the site, as well as the broader implications for understanding human evolution in Africa based on these early populations (Mercader & Martí, 2003).

Figure 22. General view of the Campo 11 site, showing the 2 × 2 m excavation grid. Adapted from Rosas et al. (2025).

Geological and Chronological Context

Geological analysis of the Río Campo region suggests the development of a meandering fluvial system during the Upper Pleistocene, characterized by sandbars and shallow channel beds overlaying a Cretaceous basement. Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) and radiocarbon (14C) dating place the occupation phases within these sedimentary units between over 44,000 and 20,000 years ago, with a lower sand unit dating back as far as 76,000 years.

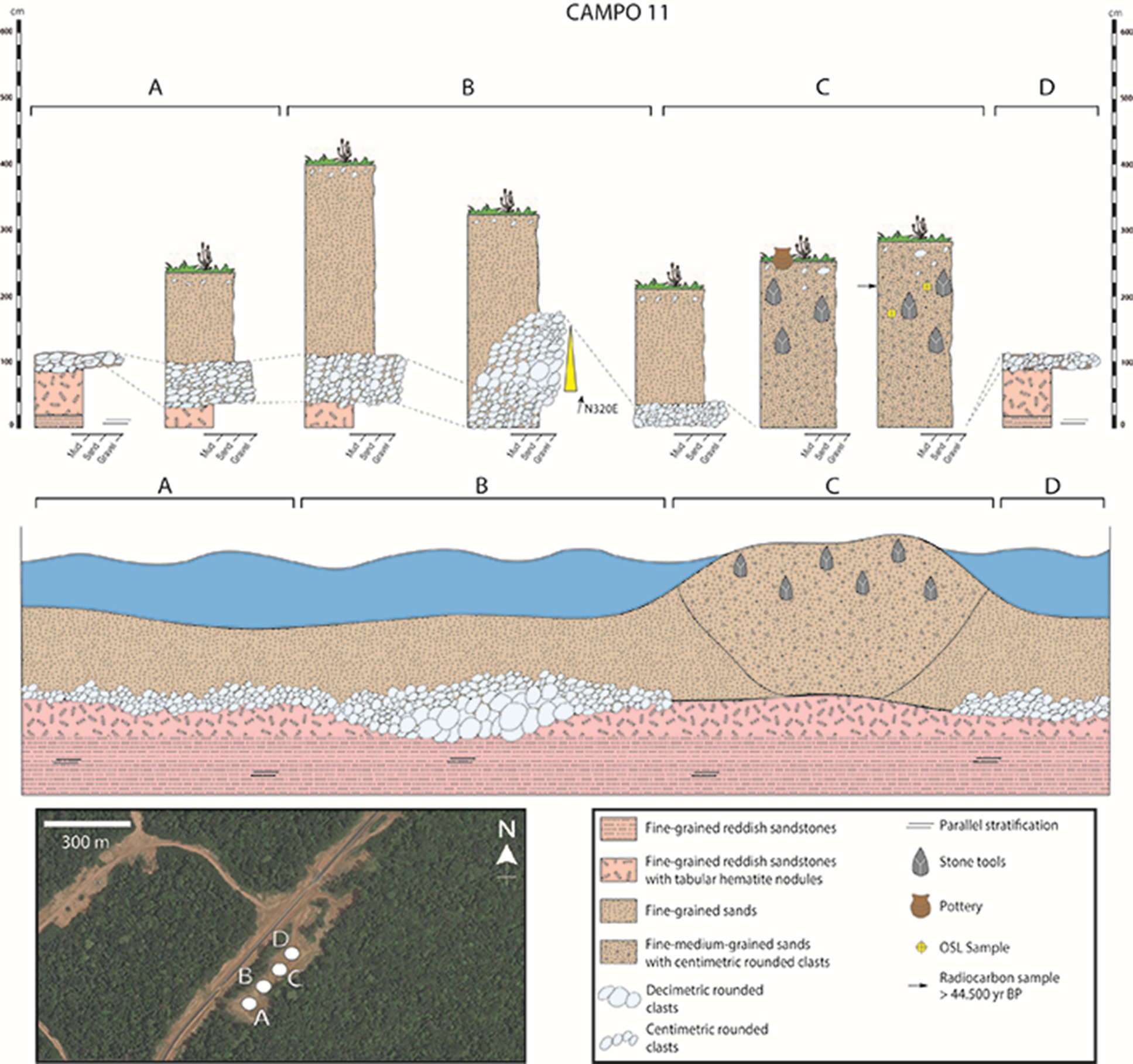

The presence of lithic assemblages within these fluvial deposits, as observed at Campo 11 (Figure 23), indicates that prehistoric populations not only inhabited these riverine landscapes, but also actively exploited the available natural resources. Within these contexts, human groups demonstrated a remarkable ability to adapt and thrive, strategically utilizing favorable circumstances to support their daily activities and long-term survival in the region.

Figure 23. Stratigraphic columns from the Campo 11 site in Equatorial Guinea, with a schematic representation of the sediment deposition environment, involving channels and bars. Includes a map showing the location of the columns along the outcrop. Bull’s-eye symbols mark the positions where OSL dating samples were collected. Adapted from Rosas et al. (2025).

Site formation processes further confirm the integrity of these deposits, as sedimentation rates, stratigraphic confinement, and the preservation state of lithic artifacts suggest minimal post-depositional movement. This has allowed us to confirm a sustained human presence during the Late Pleistocene. These findings highlight the importance of fluvial systems as ecological niches that provided water, food, and raw materials for tool production, making them attractive locations for MSA human settlement.

Lithic Industry and Technology

The lithic assemblages from the Río Campo basin reveal a homogeneous technological tradition across 16 sites, with Campo 11 standing out due to its large and well-contextualized collection of 289 artefacts. The primary raw material used was chert, complemented by quartz and quartzite.

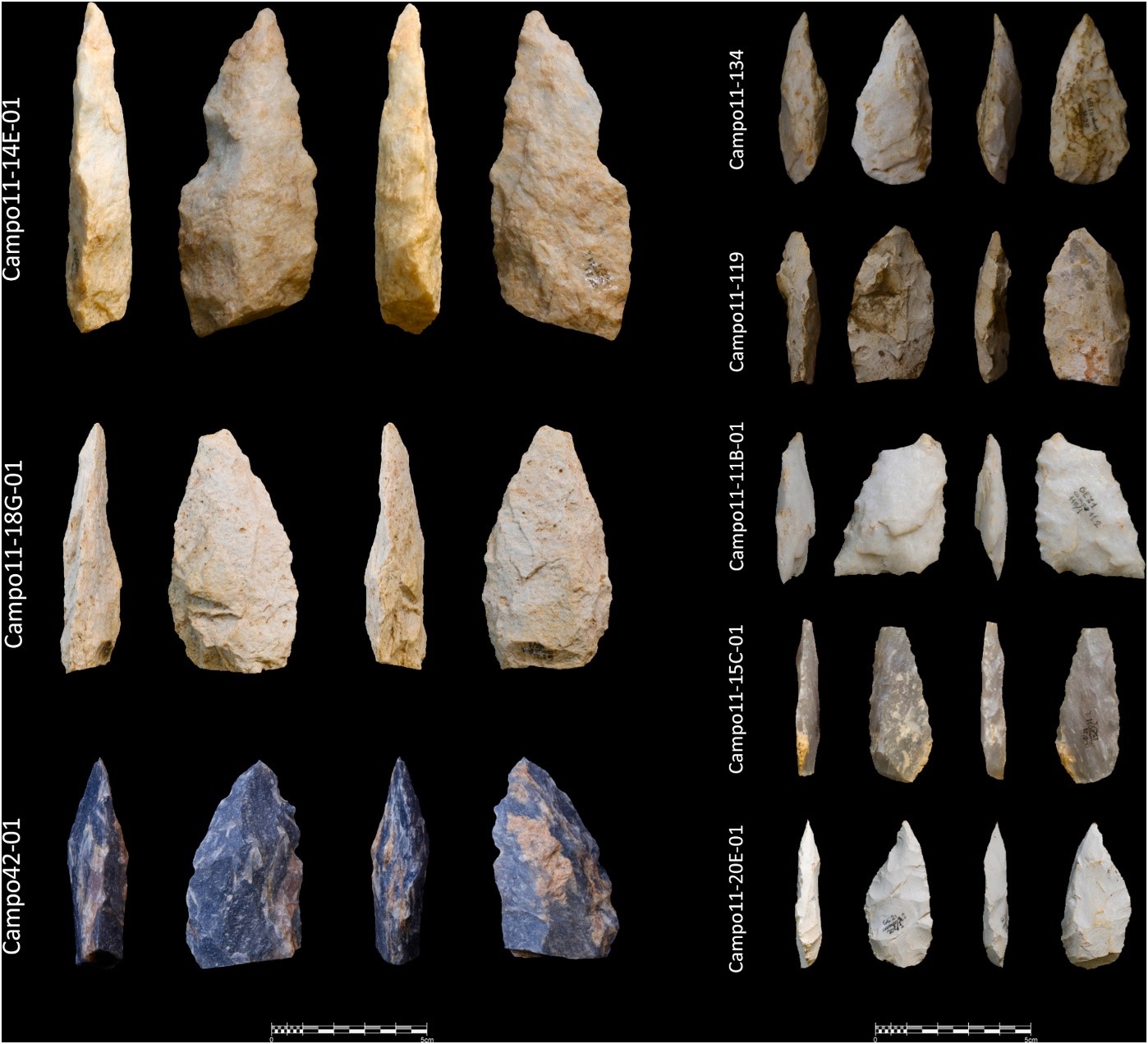

Technologically, the assemblages exhibit multiple reduction strategies. These include the use of prepared cores—particularly Levallois cores and centripetal reduction—as well as unipolar longitudinal flaking for blade production, naviform-like core exploitation, and occasional bipolar-on-anvil techniques. The retouched tool assemblage (8% at Campo 11) further reflects this complexity, featuring lanceolate bifacial points that may have served as spear tips for hunting (Figure 24), alongside robust heavy-duty tools like handaxes, cleavers, and wedges.

Figure 24. Lithic remains recovered from the Río Campo region, Equatorial Guinea. Bifacial points, including specimens from the Campo 11 and Campo 42 sites. Adapted from Rosas et al. (2025).

While smaller assemblages from other sites display more variability and less contextual clarity, comparisons with Campo 11 highlight recurring technological patterns. The diversity of reduction strategies and tool types reflects a complex technological system potentially emerging from long-term adaptation to the rainforest environments. Overall, these findings offer crucial insights into the regional cultural variability and adaptive strategies during the Late Upper Pleistocene in the Río Campo region of Equatorial Guinea, revealing the persistence of MSA technological traditions, with elements characteristic of the Acheulean-Sangoan-Lupemban transition, dating back 250,000 to 300,000 years.

Subsistence Strategies and Environmental Adaptation

While direct evidence of diet is limited due to poor organic preservation in tropical environments (Rosas et al., 2022), the technological evidence provides insights into possible subsistence strategies. The presence of heavy-duty tools such as handaxes and cleavers suggests activities related to butchery, plant processing, and woodworking. These tools would have been useful for accessing a diverse range of food resources, including large and small game, tubers, nuts, and other plant materials.

Comparisons with other MSA sites in Africa suggest that early human populations in Río Campo may have practiced broad-spectrum foraging, exploiting a variety of ecological niches within the rainforest. The presence of bifacial points further supports the idea that hunting was an important subsistence strategy, possibly targeting forest-dwelling species. This aligns with recent research indicating that early humans were capable of adapting to rainforest environments much earlier than previously thought (Cornelissen, 2003, Ben Arous et al. 2025).

Cultural and Evolutionary Implications

The Lupemban industries found in Río Campo suggest profound cultural continuity, although the scarcity of high-quality archaeological data prevents definitive conclusions. Two primary hypotheses have been proposed to explain the persistence of these technological traditions: 1) Descendants of Central African hunter-gatherers, maintaining long-standing traditions while adapting to changing ecological conditions and 2) Migrations from East Africa, incorporating MSA technologies and influencing local cultural trajectories.

The absence of Later Stone Age (LSA) technological features in the Río Campo assemblages is particularly significant. Unlike other parts of Africa where LSA bladelet production and microlithic tools became dominant, the Río Campo assemblages remain firmly rooted in MSA traditions. This suggests an extended persistence of these technologies well into the Late Pleistocene and possibly even the Holocene (Scerri et al. 2021).

Conclusions and Future Research

This study provides key insights into Pleistocene human occupation in the African rainforest but also highlights the need for further research to fill the related gaps in the archaeological record. Integrating new discoveries with genetic and paleoenvironmental studies could offer a more comprehensive picture of Central Africa’s role in Homo sapiens evolution. The Río Campo region represents a promising source of information with the potential to redefine narratives about human evolution in tropical forest environments and in turn provide exceptional insights into adaptations to other understudied ecological niches as well.

Future research should focus on: 1) Expanding excavations at key sites such as Campo 11 to obtain larger lithic assemblages and refine chronological frameworks. 2) Conducting use-wear analyses on lithic tools to reconstruct subsistence activities and tool functions. 3) Exploring new sedimentary contexts to uncover additional archaeological layers and improve environmental reconstructions. 4) Implementing palaeobotanical and faunal studies to reconstruct ancient diets and ecological conditions.

By continuing interdisciplinary investigations, we can further unravel the complexities of human adaptation and technological innovation in the challenging rainforest ecosystems of Equatorial Guinea. Understanding how early humans thrived in these environments contributes to broader discussions on the diversity of human adaptations and the evolutionary flexibility of Homo sapiens.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to the various individuals and institutions for their support during the field campaigns and laboratory analyses. We also thanks the TEA editors for their kind invitation. Funding: Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (PID2021-122356NB-I00), PIAR-CSIC, i-COOP and Palarq Foundation.

Bibliography

- Ben Arous, E., Blinkhorn, J.A., Elliott, S., Kiahtipes, C.A., N’zi, C.D., Bateman, M.D., Duval, M., Roberts, P., Patalano, R., Blackwood, A.F., Niang, K., Kouamé, E.A., Lebato, E., Hallett, E., Cerasoni, J.N., Scott, E., Ilgner, J., Alonso Escarza, M.J., Guédé, F.Y., Scerri, E.M.L., 2025. Humans in Africa’s wet tropical forests 150 thousand years ago. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08613-y.

- Cornelissen, E. 2003. On microlithic quartz industries at the end of the Pleistocene in central Africa: the evidence from Shum Laka (NW Cameroon). African Archaeological Review, 20, pp. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022830321377

- Mercader, J. and Martí, R. 2003. The Middle Stone Age occupation of Atlantic Central Africa: new evidence from Equatorial Guinea and Cameroon. In: Mercader, J. ed., Under the Canopy: The Archaeology of Tropical Rainforests. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 64–92.

- Rosas, A., García-Tabernero, A., Fidalgo, D., Fero Meñe, M., Ebana Ebana, C., Esono Mba, F., Morales, J.I. and Saladie, P. 2022. The scarcity of fossils in the African rainforest: archaeo-paleontological surveys and actualistic taphonomy in Equatorial Guinea. Historical Biology, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2022.2057226

- Rosas, A., García-Tabernero, A., Fidalgo, D., Mene, M.F., Ebana, C.E., Ornia, M., ... & Morales, J.I. (2025). Middle Stone Age (MSA) in the Atlantic rainforests of Central Africa. The case of Río Campo region in Equatorial Guinea. Quaternary Science Reviews, 349, 109132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109132

- Scerri, E.M.L., Niang, K., Candy, I., Blinkhorn, J., Mills, W., Cerasoni, J.N., Bateman, M.D., Crowther, A., Groucutt, H.S., 2021. Continuity of the Middle Stone Age into the Holocene. Scientific Reports 11, 70. 10.1038/s41598-020-79418-4.

Go back to top