Katrine Balsgaard Juul & Signe Helles Olesen

Museum Horsens, Denmark

A gendered history of archaeology

Gender archaeology follows the theoretical development of gender studies (Lindblom & Balsgaard Juul 2019; Moen & Pedersen 2025; Stig Sørensen 2000; Wylie 1991), moving through three developmental waves of challenging patriarchal research, highlighting women, and studying gender as a social construct related to power (Lindblom & Balsgaard Juul 2019, 44; Wylie 1991, 31f). The field is now in a fourth, intersectional wave, combining accumulated knowledge to uncover and communicate forgotten contributions and perspectives in archaeological thinking leading to more diverse and equal archaeological research as demonstrated in Women in Archaeology presenting the various conditions women in archaeology have been working under (López Varela 2023).

This article introduces ten female archaeologists who represent various significant roles for women in Northwestern European archaeology from 1800-2025. Some are well-known, while others deserve more attention since they – due to their gender and roles as wives, assistants, and amateurs – have not been written into the disciplinary history the way they should have. This article is dedicated to all the pioneering women, who continue to inspire us today.

Finding the ‘herstory’: Introducing the Forgotten Mothers of Archaeology project

There is a growing recognition of the need to highlight women and their contributions in archaeology. As modern history has demonstrated, there is a strong case for seeking out the forgotten history of women (Alfort 2024, 2022; Jacobsen 1995, 2022; Jexen 2021; Possing 2018). This also applies to Danish archaeology and the need to emphasize both female academics and women's roles in prehistory. This is exactly what we wish to accomplish at Museum Horsens with a new research and outreach project entitled Arkæologiens Glemte Mødre (AGM), which translates to The Forgotten Mothers of Archaeology. In this project, we are actively searching for the trailblazing women of European, and particularly Danish, archaeology from 1800-2025. In order to give these trailblazers their deserved attention, we also aim to initiate a network for and about women in Nordic archaeology entitled kvinARK, which is simultaneously a network and a dissemination project.

Why a focus on Northwestern Europe (and Denmark in particular)?

To date, gender archaeology is not as widely represented in Danish archaeology as it is globally (Balsgaard Juul 2024; Stig Sørensen 2004; Toubro Hansen 2004). In 2023, the pivotal volume Women in Archaeology was published—filled with gender archaeological studies and accounts of women's contributions to the field worldwide (López Varela 2023; see also Balsgaard Juul 2023). Denmark was not represented in the volume. For an overview of women in Danish archaeology, we must look back to 1998’s Excavating Women, wherein Lise Bender Jørgensen argued that women entered Danish archaeology late and struggled to find a place (Bender Jørgensen 1998, 214; Díaz-Andreu & Stig Sørensen 1998). Presentations of significant structural gender issues and skewed gender structures, as old as the discipline itself, were experienced by women in archaeology around the world (see López Varela 2023)…which begs the question as to whether this is still the case today in Danish archaeology (Balsgaard Juul 2024; Balsgaard Juul & Sauer 2024; Sauer 2023).

Danish archaeology was initiated by the founding fathers of the field in the early 1800s. But what of the history and contributions of women? Were women really absent in early Danish archaeology? Or have female pioneers been forgotten because they defied the gender perceptions of the 19th century, a time in which a woman’s primary role was in the home as a mother, while men were the active participants in academic society (Balsgaard Juul 2024)? Though more Danish archaeologists are now conducting serious gender archaeological studies (for example: Balsgaard Juul 2017a, 2017b, 2019; Croix 2012; Felding 2020; Felding et al. 2020; Henvig Lorenzen 2018; Javette Koefoed & Raja 2024; Lindblom & Balsgaard Juul 2019; Sauer 2023; Thirup Kastholm 2016a, 2016b), it is still easier to find female pioneers outside the borders of Denmark. The first seven examples that follow cover pioneering female archeologists from Northwestern Europe while the last three hail specifically from Denmark. Each of these women have made significant contributions to archaeology in their own right. When also seen from a gender archaeological perspective, their impacts cannot be overlooked.

1. Johanna Mestorf - the first female professor and museum director

Let us begin with one of the most famous female pioneers in archaeology: Johanna Mestorf. Mestorf (1828–1909), like many of her contemporaries, was self-taught (Gutsmiedl-Schümann et al. 2023, 288f; Mestorf 1870, 1871, 1872, 1874, 1877, 1885, 1893, 1900, 1901, 1909). In the 1860s, she translated key Scandinavian works on archaeology into German, while simultaneously beginning to write her own articles (Johnsen & Welinder 2002; Mertens 2002; Unverhau 2015a, 2015b; Unverhau & Wolter 2015; Wiell 2002). She became the first curator at the precursor to the archaeological museum at Gottorp Castle, which merged with Christian-Albrechts-University in Kiel in 1873. This gave Johanna a place in the academic world, and in 1891, she became the first female museum director at Gottorp Castle. In 1899, she was appointed honorary professor by the Prussian Ministry of Culture, and in 1909, she received an honorary doctorate (Andresen 2002; Mertens 2002; Unverhau 2015b).

Johanna’s groundbreaking contributions to cross-border archaeological collaboration are unparalleled, and her work was already celebrated during her lifetime (Müller 1897a, 1897b, 1898, 1907; Worsaae 1878, 1881). This was unusual for a woman at the time; however, it explains why she is so well know today.

2. Agda Montelius - the wife and illustrator

Agda Montelius (née Reuterskiöld) (1850-1920) was a talented illustrator, and through her drawings of countless archaeological objects, she formed the foundation on which many archaeological theories lie. Agda is mostly known for her strong engagement with women´s and humanitarian issues (Bokholm 2001). However, she was also deeply involved in the work of her internationally renowned husband – the Swedish archaeologist Oscar Montelius (Gustavsson 2020, Baudou 2012). Agda documented their travels and activities (Gustavsson 2018, 2020, Nordström 2014), became Oscar’s personal secretary and illustrator and acted as his stand-in at the museum in Stockholm, when Oscar was travelling without her (Gustavsson 2020: 121). Thus, Agda performed a myriad of archaeological tasks and, in many regards, Agda should probably have been recognized as Oscar’s co-producer of at least some of his archaeological works (Gustavsson 2020, 2025, unpublished thesis). Even though Oscar dedicated the groundbreaking work La Civilisation Primitive en Italie depuis l’introduction des Metaux ‘à ma femme’ (lit. ‘to my wife’), she was never really acknowledged for all of her (sometimes subtle) contributions to archaeology (Gustavsson 2020, 2025). Some parts of Agda’s travel diaries were even published by Oscar under his own name (Gustavsson 2020: 121), highlighting the often-unequal partnership in their work relationship. This is a further clear example of the need to pursue intersectionality as a topic in relation to gender studies of archaeological research.

3. Gertrude Bell - the politician

Gertrude Bell (1868–1926) was a multifaceted archaeologist, writer, politician, explorer and administrator (Raja 2024). Educated as a historian, she travelled extensively across the Middle East, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia (Howell 2006, 28ff). She visited and participated in archaeological excavations and published several books on her travels and observations (Bell 1896, 1907, 1911, 1914). Bell also became deeply involved in politics and participated in the Cairo Conference of 1921 in which British officials discussed Middle Eastern ‘problems’ with the intent of establishing an overall policy (Howell 2006, 238ff, 2015). Gertrude helped shape modern Iraq and in 1922 was appointed Honorary Director of Antiquities in Baghdad. There, she organized archaeological excavations and established the Baghdad Archaeological Museum (Howell 2006, 365ff; Lukitz 2006). Gertrude’s achievements as the ‘Queen of the Desert’ are a testament to the intersection of politics, archaeology, and social work for her time (Howell 2006), a trend that also continues in today’s world.

4. Agatha Christie - the writer and wife

Though famed for her detective novels, Agatha Christie (née Miller) (1890-1976) also made contributions to archaeology. After marrying archaeologist Max Mallowan in 1930, Agatha participated in several excavations in the Middle East (Morgan 2001; Raja 2024), often taking charge of photography and filming (Trümpler 2001). In fact, her experience at these digs inspired several of her stories. Mallowan dedicated books to her, but her role on the excavations was often underappreciated. Of particular interest is her book about everyday life as an archaeologist in the Middle East in the 1930s (Christie 1946; Raja 2024). Agatha’s accomplishments as a writer overshadow her subtle contributions to archaeology, but nevertheless her trailblazing work is more well-documented than that of many of the other accompanying and assisting wives of early male archaeologists.

5. Ella Margareta Kivikoski - the Baltic archaeologist

Ella Kivikoski (1901-1990) was a pioneering Finnish archaeologist known for her work on the Nordic and Baltic Iron Age (Kivikoski 1939, 1947, 1951, 1963, 1964, 1973, 1980). Her pioneering work began in 1939 when she defended her doctoral thesis as the first woman in Finnish archaeology. In 1948, she became the first female professor in archaeology at the University of Helsinki and was the first woman to become a member of the Finnish Academy of Sciences (Silver & Uino 2023, 35ff). Kivikoski’s doctoral thesis remains influential in Finnish archaeology, and her research continues to shape studies on Finnish prehistory and the roles of women in the past (Kivikoski 1939; Silver & Uino 2020, 2023; Silver 2020; see also Schaumann-Lönnquist 1991, 2004).

6. Lili Kaelas - the field archaeologist and megalith expert

Lili Kaelas (née Lüdig) (1919-2007) was a foremost figure and field archaeologist in Swedish archaeology who was particularly known for her work with megaliths from the 1940s onwards. She played a crucial role in the research and fieldwork of Axel Bagge (Bagge 1950; Bagge & Kaelas 1952), and her investigations of megaliths and their construction and chronology (and, thus, the typology of contemporary pottery) forged new paths for prehistoric archaeology (Kaelas 1951a, 1951b, 1956, 1958, 1960, 1967, 1982, 1981, 1995; see also Hjørungdal 2023, 350f). Lili became a professor of archaeology at the University of Gothenburg and her work has had a lasting impact on megalithic studies while she herself continues to be an influential figure in Swedish archaeology to this day (Hjørungdal 2023, 351).

7. Lotte Hedeager - the theoretical archaeologist

Of course, many women have contributed to theoretical archaeology, but here we have chosen to highlight Professor emerita Lotte Hedeager (1948-) to represent Northern Europe’s female contributions to archaeological theory. Hedeager’s thesis and early works in the 1970s and 80s were crucial for the development of processual archaeology (Hedeager 1978a, 1978b, 1978c, 1980, 1982, 1988, 1990, 1992a, 1992b). Furthermore, her later works from the 1990s onwards were just as crucial for the development of post-processual archaeology, particularly in Scandinavia (Hedeager 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 1999, 2000a, 2000b, 2003, 2004). Lotte’s interdisciplinary approach and scientific work have been groundbreaking in Scandinavian and European archaeology and are used as key textbooks for archaeology students both within Scandinavia as well as elsewhere around the world (Hedeager 1992 a, 1992b, 1997, 2011; Lund 2008).

8. Augusta Zangenberg - the amateur archaeologist

Augusta Zangenberg (1846–1915) was a dance instructor who became an accomplished amateur archaeologist (Hildre 2022). See Figure 18. When Zangenberg was alive, it was still not common for women to pursue formal education. Nevertheless, Augusta conducted many excavations from the 1870s onwards, leading to an extensive collection of antiquities which formed the foundation for Thisted Museum in northwest Jutland, Denmark (Fastrup 2001; Zangenberg 1910). She collaborated with archaeologists from the National Museum of Denmark on several occasions, but never reached an agreement with the eminent Danish archaeologist Sophus Müller regarding the now-famous Lindholm Høje site in Aalborg (Balsgaard Juul 2024; Ramskou 1976, 7ff). Müller once referred to Zangenberg as an overly enthusiastic amateur who ruined the research value of the burial site (Balsgaard Juul 2024, 88; Müller 1897c, 174), though Augusta’s determination appears to have been unshaken. The AGM project is still in the process of searching for further correspondence between Zangenberg and Müller beyond the few included in Thorkild Ramskou’s Lindholm Høje publication (Ramskou 1976, 7ff).

Figure 18. Wall mural created by artist Frida Still Vium in Thisted, Denmark, 2024 celebrating the crucial role of Augusta Zangenberg. Zangenberg is depicted holding a trowel (photo Museum Horsens).

9. Anna Hude - the academic and women's rights advocate

Though not an archaeologist herself, Anna Hude (1858–1934) made significant contributions to academic archaeology in Denmark. See Figure 19. As the first female historian from the University of Copenhagen, (MA 1887 and Dr. phil. 1893), Anna worked on archaeological topics such as the Danehof (a medieval Danish parliamentary institution) and the Migration Period (Hude 1893, 1908; see also Balsgaard Juul 2024). Additionally, Anna was deeply involved in the women's rights movement, evident in her research on and promotion of strong women in Antiquity (Hude 1908; see also Balsgaard Juul 2024, 88). Anna Hude was a true pioneer in the academic world (Manniche 1994, 1993), and we aim to expand the importance of her archaeological work by bringing her into sharper focus as part of the AGM project (Balsgaard Juul 2024).

Figure 19. A young Anna Hude photographed in 1881 the year before she began her studies at the University of Copenhagen (photo by Peter Most/The Royal Danish Library’s Picture Collection). /span>

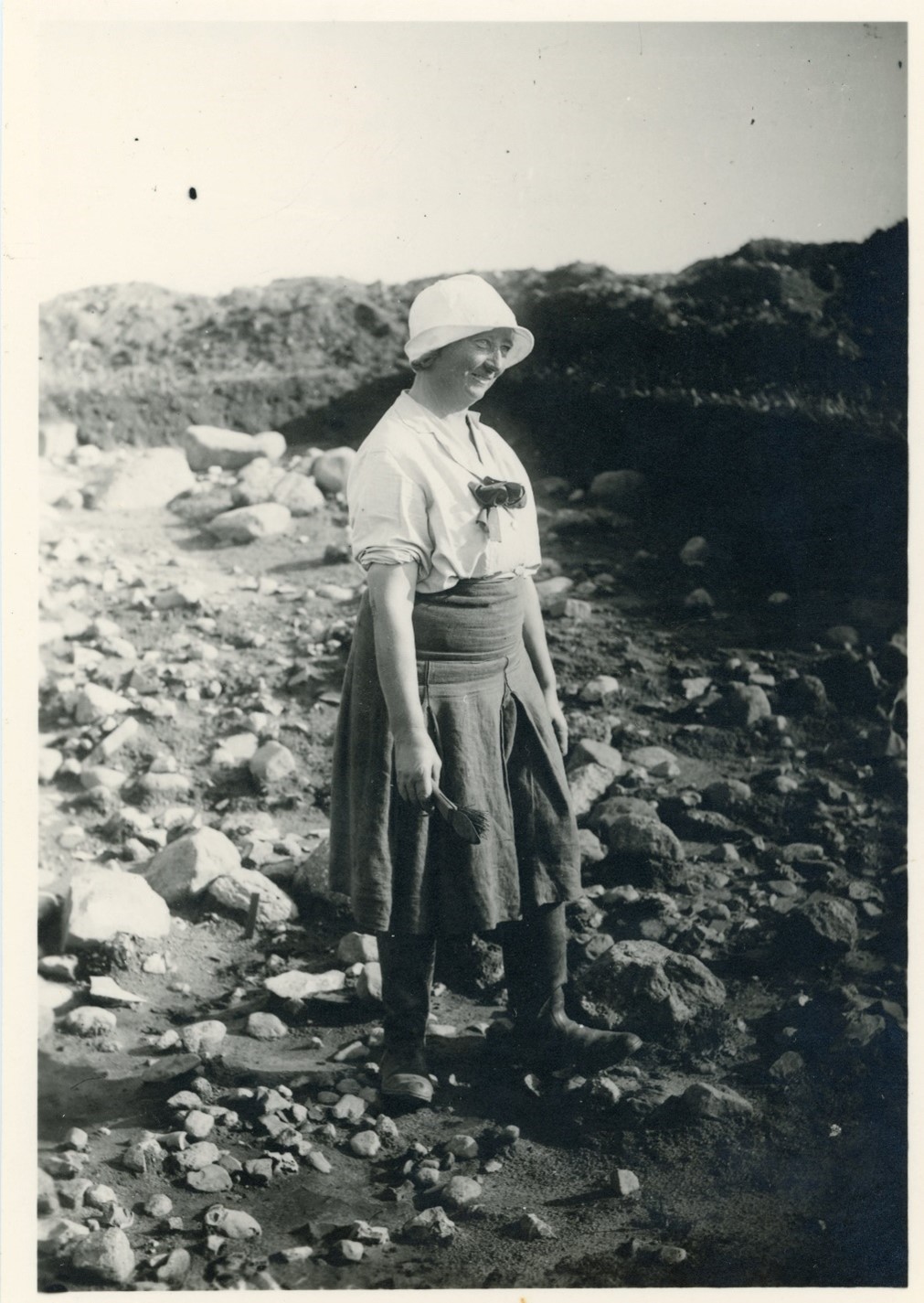

10. Anna Elsa Hornum - housekeeper, cook, and excavation manager

Anna Elsa Hornum (1877–1971) worked as a housekeeper for archaeologist Jens Winther from 1912 until his death in 1955 (Balsgaard Juul 2024, 88f; Bender Jørgensen 2000, 1980; Ravn 1998; Uldum & Chakravarty 2021). See Figure 20. She became his closest collaborator and participated in many excavations, eventually becoming known and remembered as a skilled field archaeologist. Hornum played an essential role in managing excavations and organizing finds, but she did not leave behind a written legacy (Balsgaard Juul 2024). Anna Elsa attended several archaeological congresses, including the 6th Nordic Archaeological Meeting in 1937 in Copenhagen. In 1951 she became only the second woman to be admitted to the Royal Nordic Society of Antiquarians (Bender Jørgensen 2000, 1980; Stummann Hansen 2004, 111). This highlights her essential role in Danish archaeology, making her a natural candidate for further AGM project research.

Figure 20. Anna Elsa Hornum at excavations on Langeland around 1930 (photo by permission from Rudkøbing City Historical Archive).

Intersectional gender archaeology

As the individuals presented above make evident, women have made considerable early contributions to European archaeology. However, men have dominated the field, and eclipsed the valuable contributions by women (Balsgaard Juul 2024; Lindblom & Balsgaard Juul 2019; Stig Sørensen 1998; López Varela 2023b). For example, in German archaeology, men have defined the field, and, although many women were active in early archaeology (see above), their contributions have often been written out of history or overshadowed by their male counterparts. This is due to an early and prevalent structural bias favoring the involvement of men in academia (Gutsmiedl-Schümann et al. 2023, 283).

Women in archaeology worldwide are likely familiar with this bias. Intersectional gender archaeology seeks to establish greater gender equality across the discipline. With this we can make a difference by referencing works that have been forgotten or otherwise ignored. As archaeologists, we have a responsibility to improve gender structures within our field. One way to do this is by becoming more aware of these skewed structures. The goal must be to create more space for everyone’s history. By doing so, we can broaden the field’s understanding and make a difference for future generations of archaeologists. We should not wait for ‘herstory’ to become as natural as ‘history’, but rather acknowledge that herstory has been and is ongoing.

Archaeology of the second sex?

It is more challenging to discover ‘herstory’ than history – also within the field of archaeology. The ten women presented briefly above all played an important role, but not all have received the recognition they deserved. Before archaeology became an academic field with proper training at the university level, all archaeologists were self-taught amateurs. However, within Danish archaeology there has been a tendency to put the contributions of the founding fathers of archaeology on a pedestal, without even considering or acknowledging the existence or contributions of the mothers of archaeology, thereby making them forgotten.

The fundamental question is: why? Were women less important in early archaeology due to the restraints of the prevailing society? Were their contributions somehow easier to ignore because we have been systematically taught to do so? In either case, we are left with an archaeology of ‘the second sex’ which leaves out women in the field and their long-overlooked contributions (see de Beauvoir 2021a, 2021b [1949])? Gender equality is crucial, even and especially today when women’s rights remain under attack. As archaeologists, we are trained to present the long span of history; we should also let the long span of ‘herstory’ arise to further enrich our academic field.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Anna Gustavsson for generously sharing her work and knowledge as well as to the many others who pointed us in the direction of archaeology’s female trailblazers.

Bibliography

- Alfort, Sara. 2022. Damer der var for meget. København: Gads Forlag.

- Alfort, Sara. 2024. Damer der fik nok. København: Gads Forlag.

- Andresen, Marc. 2002. “Johanna Mestorf als Prähistorikerin. Zum Konzept und Bedeutingswert ihrer archäologischen Forschungen”. In Eine Dame zwischen 500 Herren. Johanna Mestorf - Werk und Wirkung, edited by Julia K. Koch & Eva-Maria Mertens, 213-224. Berlin/München/New York: Waxmann Münster.

- Bagge, Axel. 1950. “Einleitung”. In Die Funde aus Dolmen und Ganggräbern in Schonen, Schweden I. Das Härad Villands, edited by Axel Bagge & Lili Kaleas, 7-11. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.

- Bagge, Axel & Kaelas, Lili. 1952. Die Funde aus Dolmen und Ganggräbern in Schonen, Schweden II. Die Härade Gärds, Albo, Järrestad, Ingelstad, Herrestad, Ljunits. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2017a. ON THE VERGE OF A COASTAL CULTURE: Dynamic identities in the North Sea areas AD 400-700 expressed through gender, status and regionality. Thesis. Aarhus University.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2017b. ON THE VERGE OF A COASTAL CULTURE: Dynamic identities in the North Sea areas AD 400-700 expressed through gender, status and regionality. Appendices. Aarhus University.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2019. “Static dynamics of (im)material identities in an emerging coastal culture”. In Neue Studien zur Sachsenforschung, Band 8. Early medieval waterscapes: Risks and opportunities for (im)material cultural exchange, edited by Annaert, Henrica, 140-151.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2023. “Anmeldelse. Sandra L. López Varela (red.): Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide”. KUML, Årbog for Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab, 264-266.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2024. “Hvor er Arkæologiens Glemte Mødre?”. Horsens Historier 4, edited by Merete Bøge Pedersen & Lone Seeberg, 85-95.

- Balsgaard Juul, Katrine & Sauer, Nikoline. 2024. “Begravet i tidens støv: Her er kvinderne, arkæologien glemte”. .

- Baudou, Evert. 2012. Oscar Montelius: Om tidens återkomst och kulturens vandringar. Bokförlaget Atlantis.

- Bell, Gertrude. 1896. Persian Pictures. London.

- Bell, Gertrude. 1907. Syria: The Desert and the Sown. New York: E.P. Dutton.

- Bell, Gertrude. 1911. Amurath to Amurath. London: William Heinemann Ltd.

- Bell, Gertrude. 1914. The Palace and Mosque of Ukhaidir: A Study in Early Mohammadan Architecture. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bender Jørgensen, Lise. 2000. Langelands Museum 1900-2000.

- Bender Jørgensen, Lise. 1998. “The state of Denmark. Lis Jacobsen and other women in and around archaeology”. In Excavating Women. A history of women in European archaeology, edited by Díaz-Andreu, Margarita & Stig Sørensen, Marie Louise, 214-234. Routledge.

- Bender Jørgensen, Lise. 1980. Langelands Museum 1900-1980.

- Christie, Agatha. 1946. Come, Tell me How You Live: an archaeological memoir. London: Harper Collins Publishers.

- Bokholm, Sif. 2001. En kvinnoröst i manssamhället. Agda Montelius 1850-1920. Stockholmia förlag.

- Croix, Sarah. 2012. Work and Space in rural settlements in Viking Age Scandinavia – gender perspectives. Thesis. Aarhus University.

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 2021a (1949). Det andet køn, bind 1. København: Gyldendal.

- De Beauvoir, Simone. 2021b (1949). Det andet køn, bind 2. København: Gyldendal.

- Díaz-Andreu, Margarita & Stig Sørensen, Marie Louise (eds.). 1998. Excavating Women. A history of women in European archaeology. London & New York: Routledge.

- Felding, Louise. 2020. “One Ring to Rule Them All?: Appearance and Identity of Early Nordic Bronze Age Women”. Praehistorische Zeitschrift, 2020, vol. 95 (2), 422-446.

- Felding, Louise et al. 2020. “Male Social Roles and Mobility in the Early Nordic Bronze Age. A Perspective from SE Jutland”. Danish Journal of Archaeology, 91–167.

- Gustavsson, Anna. 2018. Sveriges mest beresta kvinna. Glimtar ur Agda Montelius liv. In Sjöberg, Maria (ed.), Allvarligt talat: berättelser om livet. Makadam förlag. pp. 216-229.

- Gustavsson, Anna. 2020. Geographies of networks and knowledge production: the case of Oscar Montelius and Italy. In Roberts, Julia; Kathleen Sheppard; Ulf R. Hansson & Jonathan R. Trigg (eds), Communities and knowledge production in archaeology. Manchester University Press. pp. 109-127.

- Gustavsson, Anna Charlotta. 2025. In the archive of Agda Montelius, or How to Find the People and Practices Behind a Great Man's Work. In Coltofean, Laura; Bettina Arnold & László Bartosiewicz (eds.), Connecting People and Ideas. Networks and Networking in the History of Archaeology. Springer Cham. pp. 13-24.

- Gustavsson, Anna. Unpublished thesis. Geographies of archaeological knowledge production 1870-1910. Göteborgs universitet: https://www.gu.se/om-universitetet/hitta-person/annagustavsson

- Gutsmiedl-Schümann, Doris; Koch, Julia Katharina; Bösl, Elsbeth. 2023. “Chapter 14. Women’s Contributions to Archaeology in Germany Since the Nineteenth Century”. In Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science, edited by Sandra L. López Varela, 283-308. Springer.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1978a. "Bebyggelse, social struktur og politisk organisation i Østdanmarks ældre og yngre romertid". Fortid og Nutid, XXVII, 346-358.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1978b. "A quantitative analysis of Roman imports in Europe north of the Limes and the question of Roman-Germanic exchange". In New Directions in Scandinavian Archaeology, edited by Kristian Kristiansen & Carsten Paludan-Müller, 191-216.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1978c. "Processes towards state formation in Early Iron Age Denmark". In New Directions in Scandinavian Archaeology, edited by Kristian Kristiansen & Carsten Paludan-Müller, 217-223.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1980. "Besiedlung, sociale Struktur und politische Organisation in der älteren und jüngeren römischen Kaiserzeit Ostdänemarks”. Praehistorische Zeitschrift, 55:1, 38-109.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1982. "Settlement continuity in the villages of Stevns - an archaeological investigation". Journal of Danish Archaeology, vol. 1, København, 127-131.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1988. "The evolution of Germanic society 1-400 A.D.". In First Millenium Papers, Western Europe in the First Millenium, edited by R.F. Jones, J.H.F. Bloemers, S.L. Dyson & M. Biddle, British Archaeological Report (BAR), International Series 401, 129-144.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1990. Danmarks Jernalder - Mellem Stamme og Stat (thesis). Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1992a. Danmarks Jernalder - Mellem Stamme og Stat (thesis, 2nd edition, revised. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1992b. Iron Age Societies. From Tribe to State in Northern Europe. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1996. "'Scandza' - Folkevandringstidens nordiske oprindelsesmyte". In Nordsjøen - Handel, religion, politik. Karmøyseminaret 94/95, edited by F. Krøger & H.-R. Naley., 9-17.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1997a. Skygger af en Anden Virkelighed. Oldnordiske Myter. Samlerens Forlag, København.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1997b. "Scandinavia: Scandinavia in the Iron Age". In The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, edited by B.M. Fagan, 325-326, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 1999. "Sacred Topography: Depositions of wealth AD 400-1550 in Scandinavia". In Glyfer och Arkeologiska Rum – en vänbok til Jarl Nordbladh, edited by Gustafsson, Anders & Karlsson, Håkan. Gotarc Series A vol 3, 229-252, Göteborg.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 2000a. “Skandinavisk dyreornamentik: Symbolsk repræsentation af en førkristen kosmologi". In Old North Myths, Literature and Society. Proceedings of the 11th International Saga Conference 2-7 July 2000, edited by Barnes, Geraldine & Clunies Ross, Margaret, 126-141. (red.):. Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, Australia 2000.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 2000b. "Migration Period Europe – The formation of a political mentality". In Rituals of Power. From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, edited by Theuws, F. & Nelson, J., 15-57. Leiden: Brill., S.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 2003. "Kognitiv Topografi – ædelmetaldepoter i landskabet". In Snartemofunnene i Nytt Lys, edited by Rolfsen, Perry & Stylegar, Frans-Arne, 147-165. Oslo: Universitetets Kulturhistoriske Museer, Skrifter nr. 2.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 2004. "Dyr og andre mennesker – Mennesker og andre dyr". In Ordning mot kaos - studier av nordisk förkristen kosmologi. Vägar till Midgård 4, edited by Andrén, Anders, Jennbert, Kristina & Raudvere, Catharina, 223-256. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Hedeager, Lotte. 2011. Iron Age Myth and Materiality. An archaeology of Scandinavia AD 400-1000. London & New York: Routledge.

- Henvig Lorenzen, Daniel. 2018. The Vikings of Haithabu (8th-10th Century AD): Burials and Identity. Masters thesis. Aarhus University.

- Hjørungdal, Tove. 2023. “Chapter 17. Moving Big Slabs: Lili Kaelas and Märta Strömberg - Two Swedish Pioneers in European Megalith Research”. In Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science, edited by Sandra L. López Varela, 345-360. Springer.

- Howell, Georgina. 2006. Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Howell, Georgina (ed.). 2015. A Woman in Arabia: The Writings of the Queen of the Desert. London: Penguin.

- Hude, Anna. 1893. Danehoffet og dets Plads i Danmarks Statsforvaltning. København: Gad.

- Hude, Anna. 1908. “Middelalderen 400-1300”. In Folkenes Historie fremstillet af nordiske Historikere, bind 3, edited by Ottosen, Johan & Møller, Niels. København: Gyldendalske Boghandel.

- Javette Koefoed, Nina & Raja, Rubina. 2024. “Women of the Past, Issues for the Present”. In Women of the Past, Issues for the Present, edited by Javette Koefod, Nina & Raja, Rubina, 13-24. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Jacobsen, Grethe. 1995. Kvinder, køn og købstadslovgivning 1400-1600: lovfaste Mænd og ærlige Kvinder. Thesis. Det Kongelige Bibliotek: Museum Tusculanums Forlag.

- Jacobsen, Grethe. 2022. Magtens kvinder: før enevælden. København: Gads Forlag.

- Jexen, Gry. 2021. Kvinde kend din historie. Spejl dig i fortiden. København: Gyldendal.

- Johnsen, Barbro & Welinder, Stig. 2002. “Johanna Mestorf. The link between Swedish and continental archaeology in the Golden Age”. In Eine Dame zwischen 500 Herren. Johanna Mestorf - Werk und Wirkung, edited by Julia K. Koch & Eva-Maria Mertens, 71-102. Berlin/München/New York: Waxmann Münster.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1951a. “Den äldre megalitkeramiken under mellan-neolitikum i Sverige. Antikvariske Studier V, 7-77”.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1951b. “Till frågan om "gånggrifttidens" början i Sydskandinavien. Fornvännen 46, 346-359”.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1956. “Dolmen und Ganggräber in Schweden. Offa XV, 5-24”.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1958. “Ny typ av fotskålar från Danmark. KUML 1958, 72-82”.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1960. “Stenålderskonferens i Prag. Fornvännen 1960 (55), 144-146.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1964. “Senneolitikum i Norden. TOR X, 135-147”.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1967. “The Megalith Tombs in South Scandinavia - Migration or Cultural Influence? In Palaeohistoria Vol. XII: Neolithic Studies in Atlantic Europe. Proceedings of the Second Atlantic Colloquium, Groningen, 6-11 April 1964, 288-321”. Groningen.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1972. “Review of Märta Strömberg: Die Megalithgräber con Hagestad. Zur Problematik von Grabbauten und Grabriten. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia, Series in 8°, No. 9”. Bonn: R. Habelt Verlag.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1981. “Megaliths of the Funnel Beaker Culture in Germany and Scandinavia”. In Antiquity and Man. Essays in Honour of Glyn Daniel, edited by Colin Renfrew, 77-90. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Kaelas, Lili. 1995. “Kvinna i arkeologins högborg - och sedan”. In Arkeologiska liv. Om att leva arkeologisk, edited by Jarl Nordbladh, 105-122. Serie: C: Arkeologiska skrifter no 10. Göteborg: GOTARC.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1939. Die Eisenzeit im Auraflussgebiet. SMYA XLIII. Helsinki: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1947. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands: Bilderatlas und Text. 1. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1951. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands: Bilderatlas und Text. 2. Porvoo: WSOY.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1963. Kvarnbacken: ein Gräberfeld der jüngeren Eisenzeit auf Åland.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1964. Finlands förhistoria. Helsinki: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1973. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands: Bildwerk und Text. Helsinki: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Kivikoski, Ella. 1980. Långängsbacken: ett gravfält från yngre järnåldern på Åland. Helsingfors: Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Kjær, Hans.1920. “Nordisk Archæologmøde i Kjøbenhavn 1919”. Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, III. Række, 10. bind, udgivne af Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab, 1-62. København: I Kommision i den Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag, H.H. Thieles Bogtrykkeri.

- Lindblom, Charlotta & Balsgaard Juul, Katrine. 2019. “Pokkers køn. Tolkninger af kønsroller i yngre jernalder og vikingetid”. Tings Tale, 1, 43-64.

- López Varela, Sandra L. (ed.). 2023a. Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science. Springer.

- López Varela, Sandra L. 2023b. “”Chapter 1. Women Practicing Archaeology”. In Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science, edited by Sandra L. López Varela, 3-36. Springer.

- Lukitz, Liora. 2006. A Quest in the Middle East: Gertrude Bell and the Making of Modern Iraq. I.B. Tauris.

- Lund, Julie. (ed.) 2008. Facets of Archaeology, Essays in Honour of Lotte Hedeager on her 60th birthday. Oslo Archaeological Series vol. 10.

- Manniche, Jens Chr. 1993. "En umættelig kundskabstørst: Anna Hude, Danmarks første kvindelige historiker". In Clios døtre gennem hundrede år: i anledning af historikeren Anna Hudes disputats 1893, edited by Alenius, Marianne; Damsholt, Nanna & Rosenbeck, Bente, 141-165. København: Museum Tusculanum.

- Manniche, Jens Chr. 1994. Damen der skød på doktoren: en bog om Anna Hude. København: G.E.C. Gad.

- Mertens, Eva-Maria. 2002. “Johanna Mestorf. Lebensdaten”. In Eine Dame zwischen 500 Herren. Johanna Mestorf - Werk und Wirkung, edited by Julia K. Koch & Eva-Maria Mertens, 31-36. Berlin/München/New York: Waxmann Münster.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1870. “Der gegenwärtige Stand der Frauenfrage in Schweden”. Magasin für die Literatur des Auslandes, 16, 228-231.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1872. “Der internationale Congress der Archäologen und Anthropologen in Brüssel”. Correspondenz-Blatt der deutschen Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte Nro. 11, November 1872, 81-85 & Nro. 12, December 1872, 89-96.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1874. Der internationale archäologische und anthropologische Congress in Stockholm am 7. bis 16. August 1874. Siebente Versammlung: Hamburg.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1877. Die vaterländischen Alterthümer Schleswig-Holsteins. Ansprache an unsere Landsleute: Hamburg.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1885. Vorgeschichtliche Alterthümer aus Schleswig-Holstein. Zum Gedächtnis des fünfzigjährigen Bestehens des Museums vaterländischer Alterthümer in Kiel: Hamburg.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1893. Führer durch das Schleswig-Holsteinische Museum vaterländischer Alterthümer zu Kiel.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1900. “Moorleichen”. Die Heimat, 10, 166-168.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1901. “Danewerk und Haithabu (Hedeby)”. Mittheilungen des Anthropologischen Vereins in Schleswig-Holstein 14, 19-37: Kiel.

- Mestorf, Johanna. 1909. Führer durch das Schleswig-Holsteinische Museum vaterlänidscher Altertümer zu Kiel. Kiel.

- Moen, Marianne & Pedersen, Unn. 2025. “1. Framing gender in archaeology: snapshots from a vast and varied field”. In The Routledge Handbook of Gender in Archaeology, edited by Moen, Marianne & Pedersen, Unn, London & New York: Routledge, 3-12.

- Morgan, Janet. 2001. “Agatha Christie (1890-1976)”. In Agatha Christie and Archaeology, edited by Trümpler, Charlotte, 19-38. London: The British Museum Press.

- Müller, Sophus. 1897a. Vor Oldtid. Danmarks forhistoriske Archæologi. Kjøbenhavn: Det Nordiske Forlag.

- Müller, Sophus. 1897b. Nordische Altertumskunde. Nach Funden und Denkmälern aus Dänemark und Schleswig, 1. Bd. Steinzeit-Bronzezeit. Strassbourg.

- Müller, Sophus. 1897c. “Udsigt over Oldtidsudgravninger, foretagne for Nationalmuseet i Aarene 1893-96”. Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie, II. Række, 12. Bind, 161-124.

- Müller, Sophus. 1898. Nordische Altertumskunde. Nach Funden und Denkmälern aus Dänemark und Schleswig, 2. Bd. Eisenzeit. Strassbourg.

- Müller, Sophus. 1907. Nationalmuseet Hundrede Aar efter Grundlæggelsen. København: G.E.C. Gad.

- Possing, Birgitte. 2018. Argumenter imod kvinder: Fra demokratiets barndom til i dag. København: Strandberg Publishing.

- Nordström, Patrik, 2014. Arkeologin och livet: ett dubbelporträtt av paret Agda och Oscar Montelius genom deras brevväxling 1870-1907. Bokförlaget Atlantis.

- Ramskou, Thorkild. 1976. Lindholm Høje Gravpladsen. Nordiske Fortidsminder Serie B - in quatro, Bind 2. Udgivet af Det kgl. nordiske Oldskriftselskab. København.

- Ravn, Helle. 1998. “Markante kvinder på Langeland”. Fynske Minder, 49-64.

- Sánchez Romero, Margarita. 2023. “Chapter 10. Prehistoric Archaeology in Spain from a Feminist Perspective: Thirty Years of Reflection and Debate”. In Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science, edited by Sandra L. López Varela, 201-220. Springer.

- Sauer, Nikoline. 2023. “Kvindefald i den danske arkæologiske forskningsverden”. Arkæologisk Forum, 49, 9-13.

- Schauman-Lönnqvist, M. 1991. “Ella Kivikoskis tryckta skrifter”. Finskt Museum 97, 5–14.

- Schauman-Lönnqvist, M. 2004. “Nainen arkeologiassa – Ella Kivikoski, tutkija ja opettaja”. Arkeologia Suomessa 2001–2002, 87–100. Helsinki: Museovirasto.

- Silver, Minna. 2020. “Professori Ella Kivikoski (1901‒1990): suomalainen tiedenainen arkeologiassa, Professor Ella Kivikoski (1901‒1990): A Finnish female scientist in Archaeology”. In U. Frevert, E. Osterkamp, & G. Stock (eds.) Women in European Academies: From Patronae Scientiarium to Path-Breakers. Allea, Discourses on Intellectual Europe, Vol. 3, 267–306. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter.

- Silver, M. & Uino, P. 2020 (eds). Tiedenainen peilissä: arkeologian professori Ella Kivikosken elämä ja tutkimuskentät. Turku: Sigillum.

- Silver, Minna & Uino, Pirjo. 2023. “Professor Ella Kivikoski’s Groundbreaking Archaeological Path”, 34-53. Iskos 27. Celebrating 100 Years of Archaeology at the University of Helsinki. Past, Present, and Future.

- Skogstrand, Lisbeth. 2023. “Chapter 16. A Safe Space for Women Archaeologists? The Impact of K.A.N. on Norwegian Archaeology”. In Women in Archaeology. Intersectionalities in Practice Worldwide. Women in Engineering and Science, edited by Sandra L. López Varela, 327-344. Springer.

- Stig Sørensen, Marie Louise. 1998. “Rescue and recovery - On histiographies of female archaeologists”. In Excavating Women. A history of women in European archaeology, edited by Díaz-Andreu, Margarita & Stig Sørensen, Marie Louise, 31-60. Routledge.

- Stig Sørensen, Marie Louise. 2000. Gender Archaeology. Malden: Polity Press.

- Stig Sørensen, Marie Louis.e 2004. “Gender og arkæologisk samfundsanalyse. Hvorfor bør der være genderforskning i dansk arkæologi?” Arkæologisk Forum, 10, 22-38.

- Stummann Hansen, Steffen. 2004. Mødet i Danmark - Torden i Syd. Det Sjette Nordiske Arkæologmøde 1937. Publications from The National Museum, Studies in Archaeology & History Vol. 8.

- Thirup Kastholm, Ole. 2016a. “Spydkvinden og den myrdede. Gerdrupgraven 35 år efter”. ROMU 2015, 62-85.

- Thirup Kastholm, Ole. 2016b. “Afvigende normaler i vikingetidens gravskik? Dobbeltgraven fra Gerdrup 35 år efter”. In Død og begravet – i vikingetiden, edited by Lyngstrøm, Henriette Lyngstrøm & Ulriksen, Jens, 63-74. SAXO-Instituttet: Københavns Universitet.

- Toubro Hansen, Jette. 2004. “En forskningstradition uden gender - om manglen på genderarkæologi i dansk arkæologi”. Arkæologisk Forum, 11, 6-9.

- Trümpler, Charlotte. 2001. “A dark-room has been allotted to me … Photography and Filming by Agatha Christie on the Excavation Sites”. In Agatha Christie and Archaeology, edited by Trümpler, Charlotte, 229-257. London: The British Museum Press.

- Unverhau, Dagmar. 2015a. Ein anderes Frauenleben. Johanna Mestorf (1828-1909) und “ihr” Museum vaterländischer Altertümer bei der Universität Kiel. Teilband 1. Schriften des Archäologischen Landesmuseums, Band 13,1. Begründet durch Kurt Schietzel, Herausgeben vom Archäologischen Landesmuseum und dem Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf durch Claus von Carnap-Bornheim. Kiel/Hamburg: Wachholtz Verlag - Murmann Publishers.

- Unverhau, Dagmar. 2015b. Ein anderes Frauenleben. Johanna Mestorf (1828-1909) und “ihr” Museum vaterländischer Altertümer bei der Universität Kiel. Teilband 2. Schriften des Archäologischen Landesmuseums, Band 13,2. Begründet durch Kurt Schietzel, Herausgeben vom Archäologischen Landesmuseum und dem Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf durch Claus von Carnap-Bornheim. Kiel/Hamburg: Wachholtz Verlag - Murmann Publishers.

- Unverhau, Dagmar & Wolter, Fritz. 2015. Ein anderes Frauenleben. “Streben ist Leben” Das Tagebuch der Johanna Mestorf als Kusstodin 1873 bis 1891. Teilband 3. Schriften des Archäologischen Landesmuseums, Band 13,3. Begründet durch Kurt Schietzel, Herausgeben vom Archäologischen Landesmuseum und dem Zentrum für Baltische und Skandinavische Archäologie in der Stiftung Schleswig-Holsteinische Landesmuseen Schloss Gottorf durch Claus von Carnap-Bornheim. Kiel/Hamburg: Wachholtz Verlag - Murmann Publishers.

- Wiell, Stine. 2002. “Johanna Mestorf und einige dänische Archäologen ihres Zeitalters”. In Eine Dame zwischen 500 Herren. Johanna Mestorf - Werk und Wirkung, edited by Julia K. Koch & Eva-Maria Mertens, 147-156. Berlin/München/New York: Waxmann Münster.

- Worsaae, Jens Jacob Asmussen. 1881. Nordens Forhistorie. Efter samtidige Mindesmærker. Kjøbenhavn: Gyldendalske Boghandels Forlag (F. Hegel & Søn), Thieles Bogtrykkeri.

- Worsaae, Jens Jacob Asmussen. 1878. Die Vorgeschichte des Nordens nah gleichzeitigen Denkmälerns. Ins Deutsche übertragen von J. Mestorf. Hamburg.

- Wylie, Alison. 1991. “Gender theory and the archaeological record: why is there no archaeology of gender?”. In Engengerind Archaeology, edited by Gero, Joan & Conkey, Margaret, 31-54.

Go back to top