François Lanoë1,2,

Evelyn Combs3,

Joshua Reuther2,4 and

Ben Potter 4

1Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona

2Department of Archaeology, University of Alaska Museum of the North

3Cultural Resources, Healy Lake Tribal Council

4Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Dogs were the first animals to be domesticated. This primacy (and the way that many of us, regardless of our ethnic and cultural background, can relate to dogs) has turned dog domestication into a major research area in archaeology. Ways to study and recognize it in the archaeological record have focused on several lines of evidence: 1) ancient DNA that may show separation from ancient wolf lineages and/or connections to more recent known dog lineages; 2) morphological changes, such as size reduction and face shortening, which are typically associated with domestication; 3) changes in diet that would have resulted from dogs eating the same foods as their owners; and 4) special treatment in death, such as burial, that would be presumed to reflect special treatment in life. When and where dog domestication happened is still up for debate, although there seems to be a general agreement that it occurred initially sometime during the Late Pleistocene by Upper Palaeolithic peoples, somewhere in Eurasia. The initial “how” may have followed one or several pathways, either intentionally (for instance, as a result of taming), and/or accidentally (as a result of commensalism).

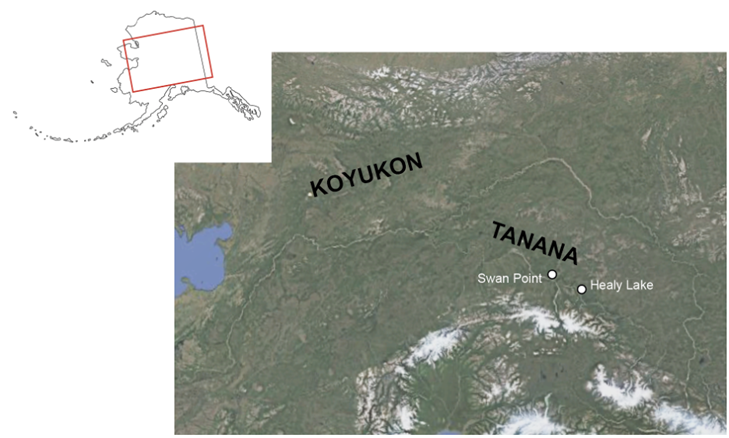

Figure 29. Map of interior Alaska and places and cultural areas mentioned in text. Hollembaek’s Hill is located near Healy Lake, and Carpenter Quarry near Swan Point. Imagery from Google Maps.

Interior (subarctic) Alaska, in northern North America (Figure 29), makes for a special place to study relationships between canids and people, as there is a long tradition among Native Dene-Athabascan communities of mutual support and survival. Nelson (1983:189) describes the relationships between dogs and people in Koyukon culture:

“Among animal inhabitants of the Koyukon world, the dog [...] stands clearly apart, unique in the society of living things. It is somehow like the other animals, somehow different; invisible spirit and visible behavior place it between the natural and human realms. And for the Koyukon people, dogs occupy a very special place in life, in many ways a very dominant one.”

Terms for owners and dogs can portray familial relationships such as the owners being referred to a ‘grandmother’ or ‘grandfather’ and dogs as ‘grandchildren.’ Nelson (1983:191) also writes about a particular story of these Koyukon close relationships to dogs in the past:

“Feelings toward dogs are also revealed by something I was told about the Distant Time. In that ancient society the dogs could talk with humans, but Raven knew that if this continued people would become too fond of them. ‘When someone lost a dog it would be just like losing a person.’ So Raven took speech away from them.”

Dogs have been, and in many cases continue to be, partners in hunting and protection, packing goods and supplies, and transportation. See Figures 30 and 31. In northern Alaska, stories of hunting animals or mythical creatures, including mammoth or mammoth-like animals, often include dogs as hunting partners (Giddings 1961; Gubser 1965). Dog teams pulling sleds are common throughout interior Alaska and, in the recent past, were used to pull freight and people and were important in maintaining communications between settlements. In the early 1900s, dog kennels in interior Alaskan communities became prominent in dog sled racing and people took immense pride in raising dog teams.

Figure 30. A Dene man and his pack dogs travel with their companion through the mountains, from Big Delta to Tanacross, Alaska, 1940. Photo by Lee Saylor (Jeany Healy Photograph Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives, UAF-2000-181-227), reproduced with permission.

Figure 31. Late Paddy Healy (Healy Lake Tribe) stands with his team and nephew, Late Alex Joe, on the frozen Healy Lake. Teams were used to haul winter fishnet harvests back home to process; a difficult, dangerous, and necessary harvest activity. Dene people relied on their dogs to feel and hear the ice better than human senses. While on the ice the body language and general agreeableness of the lead dog and team would have been paid close attention. Approximately 1940. Photo by Lee Saylor (Jeany Healy Photograph Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives, UAF-2000-181-82), reproduced with permission.

Wolves have high reverence in Native cultures as well. In some interior Alaskan Dene cultures, wolves and dogs may be considered to have separate ancestral relationships, given they did not get along with one another (Nelson 1989:158); in others, dogs and wolves may be considered part of a lineage (along with foxes, otters and wolverines) that descended from a tailed people that lived in the Alaska Range prior to Dene arrival in the region (Smith 2022:83). Some northern Dene stories describe a time in the distant, mythical past when wolf-human beings lived and hunted among people, later separating but maintaining important relationships with each other. Wolves were regarded as having similar qualities to humans with high intelligence, extraordinary senses, and the ability to cooperate. Many stories are told in which wolves acted as primary characters, and several rules govern the interactions of humans with wolves. Nelson (1983:159) describes this further: “When they parted ways [wolf-persons and humans], they agreed that wolves would sometimes make kills for people or drive game to them, as a repayment for favors given when wolves were still human… A strong sense of communality, a kind of shared identity, has held since the primordial time. Koyukon hunters still find wolf kills, left clean and unspoiled for them, and it is their right to take what is found.”

In a recent project (Lanoë et al. 2024), we aimed to explore the antiquity and nature of this strong bond between canids (dogs and wolves) and the Native peoples of Alaska. Sparking this study were the recent recovery of ancient (> 8000-year-old) canid remains from several archaeological excavations led by the University of Alaska Fairbanks in interior Alaska. Those include the Swan Point site, otherwise known as a mammoth ivory workshop and one of the oldest well-documented sites in the Americas. They also include sites located on private lands, such as the Carpenter Quarry and the Hollembaek’s Hill, whose owners have graciously supported archaeological work over the years. See Figure 32. In addition to those early archaeological sites, we looked at some of the canid remains from more recent (<1000-year-old), ancestral Dene archaeological sites. We also compiled baseline information from the very extensive paleontological and modern biological record of Alaskan canids.

Figure 32. The Hollembaek’s Hill site during excavation in 2023. Photo by Joshua Reuther, with permission.

We followed other archaeologists interested in canid domestication and likewise combined genetic, morphological, and dietary (stable isotope) lines of evidence. As is often the case in archaeology, many of the data we collected (including genetic and morphological) proved to suffer from equifinality and be consistent with several, distinct types of ecological relationships between ancient archaeological canids and people: antagonism or predation/culling of wild individuals; mutualism with wild (taming) or domesticated animals; or commensalism with wild animals. Dietary data, on the other hand, turned out to be the most informative line of evidence and permit us to infer one type of ecological relationship (to the exclusion of others) for some specimens.

The importance of paleodietary data in interior Alaska comes from the type of resources available to ancient people and canids. While specific food items (such as animal species) cannot be distinguished by paleodietary proxies such as stable isotopes, they can be grouped into three highly isotopically distinctive groups of protein-rich foodstuffs: terrestrial resources, including prey animals such as moose (elk in Europe), caribou (reindeer), hare, or ptarmigan; freshwater aquatic resources, including burbot, pike, trout, and waterfowl; and salmon, an anadromous resource. The signature of each resource group can in turn be traced back in the collagen of canid specimens, providing an estimation of its contribution to their diets.

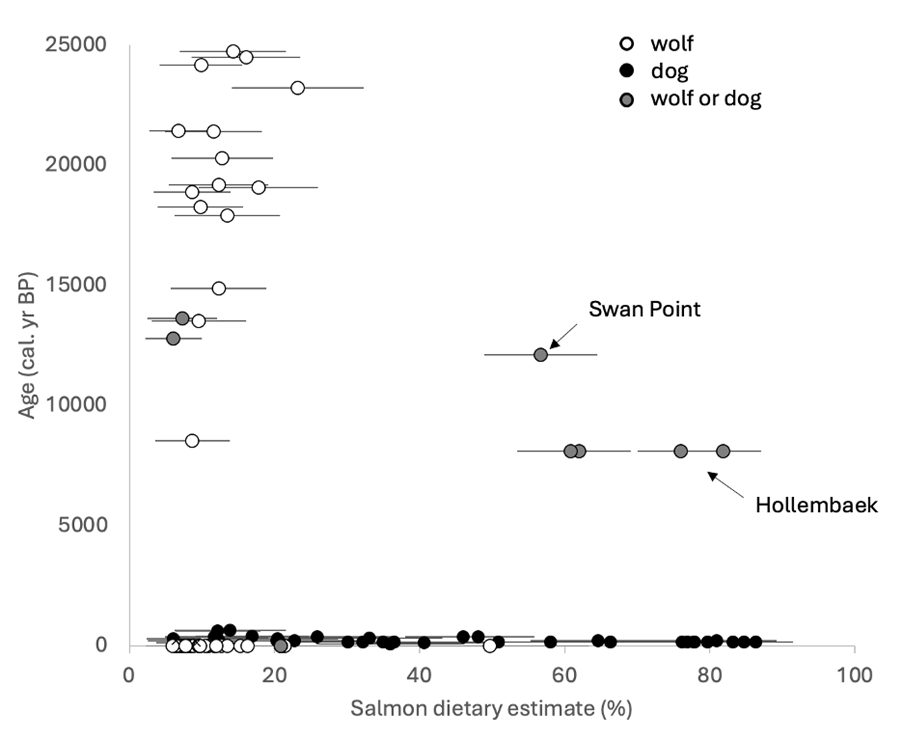

Our isotopic study of interior Alaska ancient canids showed that wolves have consistently eaten terrestrial foods both today as well as during the Ice Age (as early as 40,000 years ago). See Figure 33. Although salmon-eating wolves certainly exist, in Alaska, they are more of a coastal phenomenon in areas where salmon are available in larger quantities and over a longer time of the year. Salmon in the interior are only available for a few weeks to a few months of the summer. If wolves ate salmon there, it was never enough to register isotopically.

Figure 33. Salmon dietary estimates (at 1σ) of interior Alaskan canids, including wolves (paleontological and modern), dogs (from recent archaeological sites), and canids from early archaeological sites. Image modified from Lanoë et al. 2024.

In contrast, the diets of recent (<1000-year-old) archaeological dogs were variable, reflecting the ethnographic literature on Native Alaskan dog-feeding habits, with some dogs eating mostly or exclusively terrestrial foods, others mostly salmon, and yet others a mix of both. See Figure 33. Those dogs who ‘specialized’ in salmon were likely fed salmon that was fished in the summer, then cured and stored throughout the winter.

What of ancient (>8000-year-old) canids from archaeological sites of the interior? Dietary estimates we made on those canids turned out to be similar to those of recent dogs, with some variation from individuals who ate mostly or exclusively terrestrial foods, to individuals who ate substantial amounts of salmon. See Figure 33. Salmon intake was particularly high in three early individuals, which were named by the Healy Lake (Dene) Tribal Council as: Łii' (“dog”), a ~12,000-year-old adult from Swan Point; Ch'udelnih (“this one protects”; Figure 34) and Shłii’lai (“puppy that is precious to me”), respectively a ~8000-year-old adult and fetus/neonate from Hollembaek’s Hill. In all three cases, salmon must have been a major part of their diet, throughout the year. Shłii’lai is particularly informative since it received its salmon-rich isotopic signature as a fetus or neonate via the placenta while in utero. Its mother, thus, had substantial access to salmon during her pregnancy. If a wolf, this would have occurred during the late winter or spring, well outside the salmon run season in interior Alaska.

Figure 34. The mandible of Ch'udelnih, a 8100-years-old canid, at the Hollembaek’s Hill site. Photo by Gerad Smith, with permission.

Figure 35. Mendas Cha'ag (Healy Lake) people on their way home on the Healy River, three Mendas Cha'ag dog teams. About 1940. Photo by Lee Saylor (Jeany Healy Photograph Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks Archives, UAF-2000-181-51), reproduced with permission.

There are two ways to view our results. One involves a Western perspective that relies on genetics and morphology to characterize dogs in archaeological contexts. From this angle, some of the ancient canids we document were in a mutualistic relationship in which people fed them salmon, but we cannot distinguish which exact relationship—domestication or the taming of wild ‘pet’ wolves—was at play. In contrast, the other non-salmon-eating canids we find in ancient archaeological sites could represent any of three ecological relationships: predation; commensality; and/or mutualism in which they were also fed by people (just not given fish). Our results strengthen the significance of dietary analyses when examining human-canid relationships in archaeological contexts.

Another way to look at our results is to reflect on Indigenous knowledge about dogs. In this context, food sharing and companionship between two different species may have mattered most. Just as Native people today feed their dogs from the same fish harvests on which they themselves depend, early Alaskans shared their food with their canine companions. People did not just tolerate canids; they actively adapted their care to different environments and changing conditions and coexisted in a way that was not just about utility. This was a relationship of deep understanding and partnership. It is a story of two species growing together, learning from each other, negotiating their roles, and adapting as a team. See Figure 35. Taxonomic labeling loses some of its relevance here, particularly as Dene Athabascan communities do not make the same distinction between ‘wild’ versus ‘domesticated’, having for instance long brought in wolves to add strength and endurance to their dog teams.

It remains unclear whether some of the ancient canids we documented were intentionally buried. Should they be interpreted as such, it would speak to how meaningful the human-canid relationship was, and how canids would have been seen as beings with their own presence and spirits rather than mere tools for hunting or transportation. Many Dene Athabascan stories describe dogs as having special senses, able to detect danger or sickness before humans could. Being provided with a burial would suggest canids were considered family, deserving of care even in death. This deeply personal way of seeing animals hints that the relationship was a two-way process—canids were not just shaped by humans; they shaped human lives, too.

At its heart, this research is not just about the past—it is about continuity. The relationships between humans and dogs today in Indigenous communities across Alaska are living proof of an ancient partnership that has endured through time. As their ancestors did, people still rely on their dogs for companionship, protection, and work. And maybe—just maybe—the reason dogs have stayed by their side all these years is not just because people needed them, but because the dogs chose to stay.

Bibliography

- Giddings, J.L. 1961. Kobuk River People. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Gubser, N.J. 1965. The Nunamiut Eskimos, Hunters of Caribou. Yale University Press.

- Lanoë, F.B., J.D. Reuther, S. Fields, B.A. Potter, G. Smith, H. McKinney, C.M. Halffman, C.E. Holmes, R. Mills, B. Crass, R. Frome, K. Hildebrandt, R. Sattler, S. Shirar, A. de Flamingh, B.M. Kemp, R.S. Malhi, and K.E. Witt. 2024. “Late Pleistocene onset of human-canid mutualistic interactions in interior Alaska”. Science Advances 10: eads1335.

- Nelson, R.K. 1983. Make Prayers to the Raven: A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest. The University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, G. 2022. The Gift of the Middle Tanana: Dene Pre-Colonial History in the Alaskan Interior. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Go back to top