Mark Munn

The Pennsylvania State University

If Discovery were personified, as the ancients did with Victory or Fortune and like concepts, then she would be the guiding spirit of archaeology. In addition, were this the case, one of her favourite domains would surely be Anatolia, or Asia Minor (modern Turkey). A leading devotee of Discovery, British officer and classicist William Martin Leake, testified to her presence in Anatolia in the introduction to his Journal of a Tour in Asia Minor, when he wrote that for those interested in classical antiquity, “there is no country that now affords so fertile a field of discovery as Asia Minor” (Leake, 1824, p. iii). This rang true in 1800, when Leake made his tour, and does so still today. Discovery revealed to Leake the realities of many places known until then only from classical texts. Discovery, for Leake, also opened the door to ancient Phrygia, a realm dimly known only from over the horizon of classical myth: the land of Midas.

Traveling southeast from Eskişehir on a journey that would take him to Konya in central Turkey and beyond, Leake turned aside to spend a day “viewing some monuments of antiquity, which were reported to us at Seid-el-Gházi” (Seyitgazi) (Leake, 1824, p. 21). This brought him into the wooded hill country that we now know as the Phrygian highlands. There he discovered (or was the first to describe) the grand carved façade that has come to be known as the Midas Monument. See Figures 8 and 9. The Midas Monument is a rock face carved in the shape of a building façade with a gabled pediment. It measures over sixteen meters in height, is decorated with geometric patterns and with a doorway niche at the center of its base. Over the top is an inscription carved in half-meter tall letters that, as Leake noted, resemble archaic Greek lettering. Although the language was obscure, Leake could recognize the name and titles of Midas. By the name of this king, and from what he knew of the history and classical geography of central Anatolia, Leake deduced that this was a Phrygian monument. With his description of this and a handful of other rock-cut monuments in the vicinity, the archaeology of Phrygia was born.

After devoting fifteen pages to his detour into the highlands and to the valley overlooked by the Midas Monument, Leake remarks: “I cannot quit the subject of this interesting valley without expressing a wish that future travellers, who may cross Asia Minor by the routes of Eski-shehr or Kutáya, will employ a day or two in a more complete examination of it than circumstances allowed to us” (Leake 1824, p. 35). Discovery has since rewarded many of those who followed Leake’s advice.

Figure 8. The Midas Monument behind the village of Yazilikaya. Photo by author.

Figure 9. The Midas Monument, with the author and Lynn Roller. Photo by C. A. Munn.

By the mid-twentieth century, seven more large façades, each four meters or more in height and at least eleven smaller façades were identified. Most of these were recorded in that magisterial work of archaeological topography, The Highlands of Phrygia, published in 1971 by the Dutch classicist and archaeologist, C.H. Emilie Haspels (see Bilgin 2022-2025 for recent images and bibliography). Haspels and her predecessors recognized that the majority of these façades (certainly all of the monumental ones) were archaic in date, that is, they pre-dated the arrival of the Persians in Anatolia in the mid-sixth century BC. Many have regarded the Midas Monument to be contemporary to its namesake, the famous King Midas of Phrygia who is known from contemporary Assyrian records to have reigned in the last decades of the eighth century BC. Other scholars (among whom I count myself) have considered the Midas Monument to be a later dedication to the memory of that great Phrygian king, and therefore see it and most other façades as works of the first half of the sixth century BC, when Phrygia was part of the Lydian kingdom (see Berndt-Ersöz, 2006, pp. 89-142; Summers, 2023).

The interpretation of the function and meaning of these façades is tied very closely with the question of dating. For over a century the Midas Monument was believed to be funerary, marking either the tomb of that king or his cenotaph. This was not an unreasonable hypothesis, given that there are in fact carved chamber tombs throughout the highlands ranging in date from the fifth century BC to the Roman era. Exploratory digging and close study eventually proved that these façades did not mark tombs, but were instead votive or cultic monuments. Façades both large and small were settings for the appearance of a goddess standing in the doorway niche, seen as if she were standing in a shrine. Several of the smaller façades had images of the goddess carved in high relief, all much eroded when they were first recorded and photographed, but all now sadly vandalized or completely destroyed by treasure-seekers. Most niches of the larger façades had no fixed images, but cuttings in the floor or ceiling indicate that moveable statues were placed in them. This is the case with the Midas Monument, where Phrygian inscriptions scratched in the niche give the goddess’s name: MATAR, the Phrygian Mother. Monuments such as these honoured the goddess known to the Greeks as the Mother of the Gods, also by one of her Phrygian epithets: Kybele (see Roller, 1999, pp. 63-115; Munn 2006, pp. 56-177).

Travel into the Phrygian highlands in Leake’s day (and for more than a century thereafter) required horses and camping equipment for any extended stay. Thereafter, and until about fifty years ago, exploration required a sturdy all-terrain vehicle, as few improved roads traversed this region. In addition, many of the monuments were off the beaten path and were otherwise hard to locate without a local guide. The decades since have seen much improvement in terms of paved roads and even signage that identifies most of the best-known monuments. Turkish authorities have done much to encourage tourism, both to appreciate the archaeological monuments in what is signposted as the ‘Frig Vadisi,’ or ‘Phrygian Valley’, and to promote wilderness hiking on marked paths through the scenic highlands. Even now, as tour busses bring groups to see the Midas Monument, it is not impossible for visitors to also encounter Discovery in the highlands!

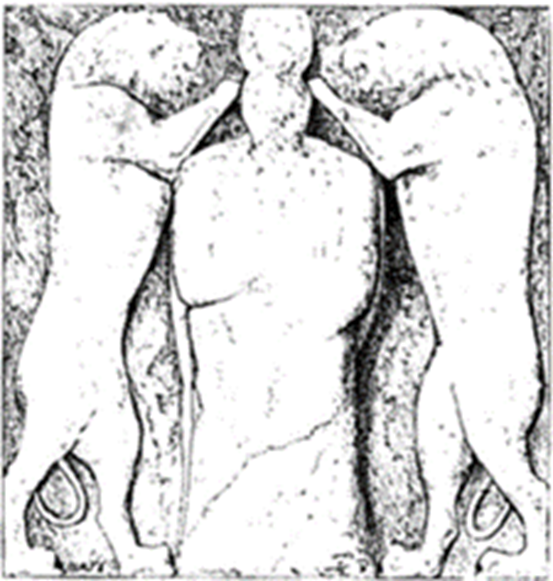

In April of this past year, encouraged by Lynn Roller, friend and leading scholar on the history of the Phrygian Mother and accompanied by my wife and daughter, I devoted two days to seeing as many of the known and surviving façades as we could. On an earlier trip I had seen the Midas Monument and the extensive archaeological site associated with it. This time I was keen to see the façade that has been regarded as the most impressive in the Phrygian highlands after the Midas Monument: that known as Arslan (or Aslan) Kaya, “Lion Rock”. See Figure 10. Carved on a free-standing spire of the local volcanic tuff conglomerate, this seven-meter tall façade has sphinxes standing in the pediment, a gigantic lion standing upright on one side of the rock, and most remarkably, a 2.2 meter tall image of the Phrygian goddess standing inside the doorway niche, with two lions rearing up on either side of her. See Figures 11 and 12. Time and willful destruction have not been kind to Arslan Kaya, however. Its surviving features are all weather-worn, damaged by nature and more recently defaced by treasure-seekers, who have dynamited part of the façade and have completely hacked away the image of the goddess that had originally been found in the niche in its entirety. Before her image was so callously destroyed, Arslan Kaya was the only monumental façade with an image of the Phrygian Mother. Now seeing the monument in person for the first time, I had to content myself by photographing it in favourable morning light, recording as much of its surviving features as I could.

Figure 10. The Arslan Kaya monument. Photo by author.

Figure 11. The Arslan Kaya goddess and her lions as drawn by Ramsay 1884.

Figure 12. The remains of the Arslan Kaya goddess and her lions today. Photo by author.

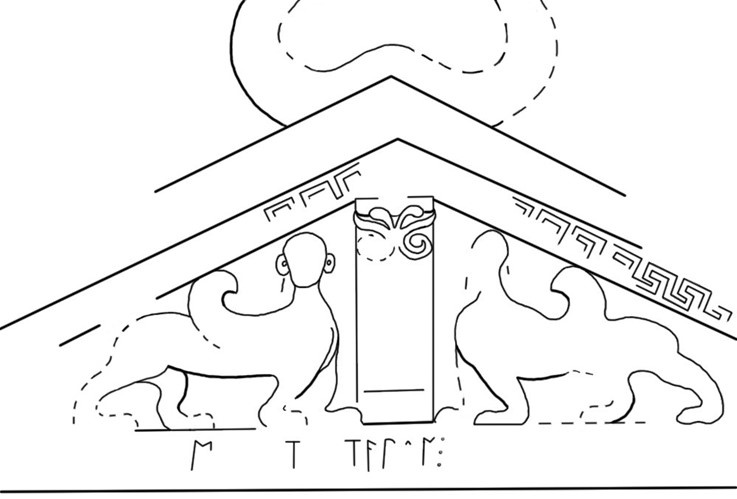

The unique sculptural features of Arslan Kaya have attracted scholarly attention ever since it was first described by William Mitchell Ramsay in 1884. Ramsay also observed that there was an inscription engraved in what he called “the tall narrow Phrygian characters” on the horizontal beam at the base of the pediment. But Ramsay goes on to note at that time that “the inscription is hopelessly obliterated” (Ramsay, 1884, p. 243). A few years after Ramsay, Arslan Kaya was visited by Alfred Körte. In his description of the monument, Körte took note of the inscription, which he suggested would probably never be deciphered. But he went on to remark that in a photograph taken in particularly favorable lighting he believed he could make out the letters ‘τ.τματεραν’ (Körte, 1898, p. 93). Investigators who followed after Körte repeated his observation, with reserve, including Haspels, who added the comment, “The inscription is worn, and to me illegible” (Haspels, 1971, p. 294). Eventually, even Körte’s tentative reading was rejected as untenable by Claude Brixhe and Michel Lejeune, in their definitive corpus of Phrygian inscriptions (Brixhe and Lejeune, 1984, pp. 43-44). Since then, all commentators have referred to the authority of Brixhe and Lejeune and the illegibility of the inscription.

Figure 13. Detail of the Arslan Kaya pediment showing visible traces. Photo by the author.

Figure 14. Tracing of Figure 6 showing the surviving traces of letters and decorative features. Reconstruction by the author.

However, in reviewing the published record of the sorry state of the inscription on Arslan Kaya and examining the photographs I had taken, I could see clear traces of most of the letters that Körte reported. See Figures 13 and 14. Indeed, they appear not only in my photographs, but can be discerned also in the excellent photographs taken more than seventy years ago by Haspels. The traces are visible under the base of the central king post and under the paws of the sphinxes, where the inscribed surface was given slight shelter by those overhanging features. Working closely from these traces, and from the photographs taken by Körte which were provided to me by the German Archaeological Institute in Istanbul, I could also recognize that Brixhe and Lejeune had erroneously reported the spacings of some of these letters, a fact that had led them to discount entirely the reading that Körte had suggested. As a result, I can say that Körte has been vindicated. His reading—with some improvements—should now be considered verified. Transcribing the Phrygian letters into Latin characters, the word MATERAN is readable in the center of the inscribed surface, with a few definite letters before and after it (See Figure 15 for the restored reading, and Munn 2024 for the full report). This is the name or title of the Phrygian Mother, MATAR in the accusative case, where she is the object of a sentence that most likely gave the name and titles of the person who dedicated this monument to her. While most of the inscription, (which was more exposed to the elements than this central portion) is indeed illegible, we can claim at least that 20% of the original inscription has been read, and that it gives the name of the goddess whose image once stood prominently in the niche directly below. Her name survives even if her image does not.

Figure 15. Legible letters on the Arslan Kaya monument compiled from multiple images. Compilation after Munn 2024.

This was not the only discovery made possible by the study of my recent photographs. They reveal traces of volutes below the top of the central king post of the pediment, with evidence of the lobes of a palmette above the volutes. See Figures 13 and 14. This sort of stylized floral palmette is characteristic of terracotta architectural decorations of the early sixth century BC that have been found at the Phrygian capital of Gordion and at the Lydian capital of Sardis. They are products of the era when the Lydian empire under kings Alyattes and Croesus was at its height, embracing all of Phrygia. This chronologically significant decorative motif had not previously been recognized, but it reinforces the evidence that Arslan Kaya, possibly along with the majority of the great Phrygian façades, was a creation of the era of Lydian dominion over Phrygian lands. Discovery has served the Phrygian Mother by not only preserving her name, but also by indicating to us why the Greeks, aware of this great goddess of Anatolia, consistently described her as the object of veneration by both Lydians and Phrygians.

Bibliography

- Berndt-Ersöz, Susanne. 2006. Phrygian Rock-Cut Shrines: Structure, Function, and Cult Practice (Culture and History of the Ancient Near East vol. 25). Leiden and Boston: Brill

- Bilgin, Bora. 2022-2025. Phrygian Monuments. https://www.phrygianmonuments.com/

- Brixhe, Claude, and Lejeune, Michel. 1984. Corpus des Inscriptions Paléo-Phrygiennes, 2 vols. Paris: Recherche sur les civilisations

- Haspels, C.H. Emilie. 1971 The Highlands of Phrygia: Sites and Monuments, 2 vols. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Körte, Alfred. 1898. “Kleinasiatische Studien III. Die phrygische Felsdenkmäler”, Athenische Mitteilungen 23, pp. 80-153

- Leake, Willian M. 1824. Journal of a Tour in Asia Minor, with comparative remarks on the Ancient and Modern Geography of that Country. London: John Murray

- Munn, Mark. 2006. The Mother of the Gods, Athens, and the Tyranny of Asia: A Study of Sovereignty in Ancient Religion. Berkely, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press

- –- 2024.“The Phrygian Inscription W-03 on the Arslan Kaya Monument”, Kadmos, Zeitschrift für vor- und frühgriechische Epigraphik 63, pp. 79-92

- Ramsay, Willian M. 1884. “Sepulchral Customs in Ancient Phrygia”, Journal of Hellenic Studies 5, pp. 241-262

- Roller, Lynn. 1999. In Search of God the Mother: The Cult of Anatolian Cybele. Berkely, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press

- Summers, Geoffrey D. 2023. “Notes on Phrygian Architecture: A Sixth-Century BCE Date for the Midas Monument at Midas City”, American Journal of Archaeology 127, pp. 189-207

Go back to top