Mobility and Social Integration of the Formerly Enslaved in the Ancient Greek World

Christian Ammitzbøll Thomsen

The National Museum of Denmark

The ancient Greek world was famously a world on the move. The communities of the eastern Mediterranean depended on each other for the necessities of life, including human resources. Funerary inscriptions from practically all ancient Greek city-states testify to the constant movement and exchange of people between cities and to the presence of considerable migrant communities.

In 2020, aided by a grant from Danish Council for Independent Research, I was able to put to together a small international and interdisciplinary research team under the auspices of the project ‘Migrants and Membership Regimes’ to investigate how and under what circumstances migration shaped the lives of ancient Greek city-state communities. The free male migrant stands dominant in the epigraphic evidence (that is to say, those written records inscribed on stone); but the project set itself the challenge of examining how different attributes—gender, status, wealth, language—shaped the migrant experience and outcomes in the ancient Greek world.

One obvious (but also partly obscure) migration was that of enslaved individuals from the periphery of the Greek world into Greek cities. The exact scale of these migrations is debated, but it is generally agreed that slavery was a foundational institution for ancient Greek society. It touched every aspect of life: economic, social, religious, and political. Slavery’s social embeddedness presents a methodological problem. Slavery as an institution was never the object of the sustained interest of ancient writers, and only rarely do individual slaves emerge in the evidence. While they were always there in the background – always in the picture so to say – they were never the subject of focus.

Delphi and Corpus

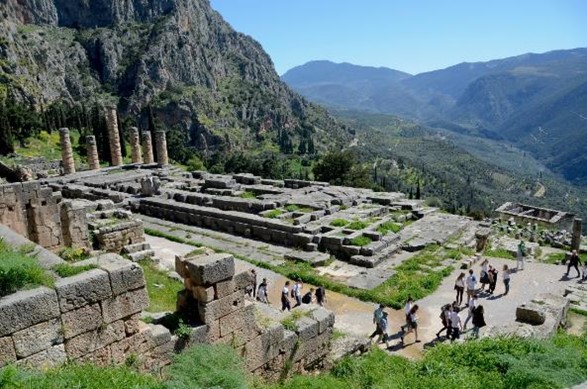

That ubiquitous, but obscured presence finds a striking example at the sanctuary of the god Apollo in Delphi. The sanctuary—home to not only the famous oracle, but also to the Pythian Games, a quadrennial festival on par with that celebrated in Olympia—was a center of the ancient Greek world and a place of display for the Greek city-states. The so-called Sacred Way that meanders up the mountain, through the sanctuary, past Apollo’s temple and the monumental theatre to the hippodrome, is lined with the treasuries of the Greek cities. See Figure 16. The sanctuary housed the most precious and impressive gifts bestowed upon Apollo by the citizens of this or that city state, reminding all visitors of their surplus wealth and piety. Among these are monuments to royal families and monuments celebrating military victories.

Behind the display, the massive retaining wall turns out to be covered in writing. Said writing is not in continuous text, but in smoothed patches on the wall, each carrying a document, inscribed in tiny (about 1 cm tall) letters, relating to the freeing of one or more enslaved persons. See Figure 17. These inscriptions are a kind of deeds of sale attesting to the transfer of ownership of a person from a free person, usually a citizen of Delphi, to Apollo, the god of the sanctuary, who assumes ownership for the expressed purpose of setting said person free.

Figure 16. Tourists make their way up the Sacred Way in Delphi in the May heat of 2024.

If the lives of the enslaved and the lives of the formerly enslaved are often only poorly attested in our evidence, the point of transition from one state to another (manumission) is precisely the opposite. In addition to the manumission documents from Delphi, similar inscribed documents have been recovered from Lokris, Boiotia, Aitolia, Thessaly, Lakonia and Kalymnos. The total evidence amounts to several thousand documents. It would not be unreasonable to call manumission one of the most well-attested social events of the ancient Greek world (though death, of course, takes the prize).

Figure 17. Inscribed retaining wall along the Sacred Way and the Treasury of the Athenians.

That fact translates into a curious methodological and practical problem. Firstly, the study of freed persons’ mobility depends almost entirely on the records that granted this status, which attest mainly to the assumptions and desires of the slave-owners, and only indirectly to the experiences of the freed through whatever conclusions slave owners drew from interacting with their former slaves. Secondly, the material evidence is vast, uneven, and unwieldly.

These problems multiply when comparing inscriptions across sites (and thereby also across time and legal and social conditions). But even within the site of Delphi, gaining a full view of the evidence is not an easy task. The recent publication of Corpus des inscriptions de Delphes V.1 (2020) and V.2 (2023) by Dominique Mulliez, collects and reedits the manumission documents inscribed at Delphi. But Mulliez’ edition does a lot more than correct our counting. It rests on a new and careful reading, aided, of course, by the published observations of many brilliant epigraphers that read the inscriptions. The result is that many of the texts are more reliable. In other words, the publication of these two volumes is a game changer for the study of ancient slavery, manumission, freed persons, and their mobility.

The Documents

A total of 1272 documents are preserved from c. 200 BCE to 50 CE. The documents specify the seller by name, the price and the conditions of the sale, but also record basic information regarding the person being sold. Presumably this was in conformity with regular deeds of sale: the name, gender and origin of the person in question.

Names clearly served to distinguish one slave from another. But they also betray the owners’ fascination with the exotic (some slaves were given foreign names that did not match their origin) or with the virtues that Greek slaveowners hoped to find or instill in their unfree laborers: we find sobriquets like ‘Pleasant’ (Hedeia, CID V.1 37), ‘Moderate’ (Sophrona, CID V.1 54), and ‘Remaining’ (Paramona, CID V.1 133), to name only a few. If the giving of such names reflected a hope that the enslaved would conform, they may also concomitantly intimate that the enslaved themselves felt or acted quite the opposite.

Gender and origin also helped identify slaves and were clearly important properties. Work—which included care work—in the ancient Greek household was gendered, and the high proportion of women among the manumitted (some 65%) is usually explained by owners’ affection for their caregiving slaves, who were disproportionately female. The role of gender in shaping the institution of slavery, the experience of being enslaved and eventual outcomes for the unfree, is an important emerging field of inquiry, and the subject of a forthcoming volume edited by Andrew Lepke, Lene Rubinstein and Claire Taylor. The volume explores, among other things, the dynamics of reproduction and reproductive strategies (D. Kamen), and points (C. Taylor) to the gendered nature of the transaction: female slaves were overwhelmingly freed by female owners.

The documents also make plain that slavery and migration were intrinsically linked. At least 40% of the enslaved in Delphi had been extracted—and in all likelihood forcibly so—from their homes and found themselves in a foreign land with strange customs and an unfamiliar language (an Aristotelian treatise on household management counsels the purchase of slaves with different origins, in order that the enslaved members of the house do not share a language unknown to their masters). That proportion, however, likely reflects a preference for locally-born slaves for care work, that is for enslaved persons whose native (and perhaps only) language was Greek and who had no personal recollection of a life of freedom. But the local supply clearly did not meet the demand. In a forthcoming article co-authored with David Lewis (Edinburgh), I explore the evidence from Delphi with similar manumission documents from Locris and the funerary record of Rhodes to trace out the patterns of slave imports to these places. We are able to trace the expansion of slaving zones along the periphery of the Greek world, as that world itself expanded over the course of the Hellenistic period, i.e., during the three centuries that followed the conquests of Alexander the Great. Furthermore, there is good evidence that gender and origin intersected in certain preferences. Male slaves from Cappadocia, for instance, and female slaves from Thrace, can be seen in the preferences of slave buyers in both Delphi and Rhodes.

Figure 18. Inscribed manumission documents.

The Delphic and other manumission documents are evidence that most (if not all) Greek cities were home to substantial populations of formerly enslaved persons. See Figure 18. One strain of my own research, which is shaping into a book, is concerned with documenting these lives and in particular post-enslavement mobility. In the Delphic documents, the abstract concept of freedom is glossed as “going where one wants, and doing as one pleases”, indicating that freedom was first and foremost understood as the freedom of movement. A key issue, then, is the following: where did the formerly enslaved go when they were finally allowed to go where they wanted? The manumission documents provide a partial and heartbreaking answer: nowhere. About a third of the manumission documents include a so-called ‘paramone clause’, which stipulated that the freed person was required to remain with their owners—usually until the owner died—performing all of the same tasks and with the same obedience as they had as slaves. But what about those who were not required to stay?

I must pause to note that the evidence, such as it is, is incapable of recording the potential return of some former slaves to their home communities. However, there are indications that staying around was the dominant norm. In one case, a man from Achaia (in the Peloponnese) travelled to Delphi to free his slave and specified that he, the freed slave, could not under the terms of the agreement, set foot in Achaia ever again. The provision is unique and tickles the imagination (did this slave witness a crime?). More importantly, it lays bare the assumption that freed persons would be expected to want to remain in the same community as their former owners. There may have been attachments: for example, family and especially children that remained enslaved, or there may have been fears of a life in the unknown. Certainly, the institutional protection for the newly freed encouraged sticking around.

In Delphi, citizens and magistrates witnessed and guaranteed the manumission and the laws of the city made the defense—even the violent defense—of a freed person’s freedom an unimpeachable action. Elsewhere in the Greek world the entire citizenry swore to protect the freedom of freed persons. But that very earnest commitment to respecting a manumission ended at the border of a city’s territory. That limitation was to an extent a reflection of the politically fragmented world of the ancient Greek city states. A closer look at the material suggests that the retention of a substantial pool of non-citizens with no better options on hand could work as a human resource buffer in times of need.

In any Greek city, social and political reproduction were almost always at a risk. Cities needed labour. Gods expected the usual sacrifices. But equally important was the fact that cities required citizens. They needed people for the defense of the city and for the running of institutions. The freed population represented a pool of human resources that could be tapped into in case of need. The latter part was important, in case of pressing need. In crises, members of the freed population could be enrolled as citizens. This was not necessarily uncontroversial. In a handful of manumission documents, owners give (or withhold) their consent for their former slaves to become enrolled in the citizenry, suggesting that owners had a say in whom could be tapped for citizenship. Such were only one type of provision found in the documents. Owners added what seems to be an endless list of idiosyncratic provisions to the Delphic manumission agreements. Perhaps this is evidence of the extreme prerogative of slave owners in organizing the social world of Hellenistic Delphi. Perhaps further studies of the documents will detect patterns that represent legal changes, in turn reflecting new common challenges to the community. The potential of this human resource is perhaps most clearly expressed at the private level: when families were in need of male heirs. In some cases, enslaved children were adopted (it is an easy assumption that their adoptive fathers were probably also their biological fathers) and freed women could be married into the ranks of the citizens.

Migration of the enslaved was, therefore, twofold and perhaps played out over generations. One individual’s extraction from the periphery of the Greek world could lead to sale in a community like Delphi. Under the right circumstances, this could eventually lead to migration through the orders of the city from slave, to freed person to citizen, with all the duties and privileges that citizenship entailed (including owning slaves of their own). What at the outset might look to be the stable and stale institutions of the Greek cities begins to look quite dynamic. The continuous trafficking of enslaved labour into ancient Greek cities provided an economic basis for those societies, but, by and by, that same workforce could be converted to plug the holes of the familial or social order whenever they occurred and for whatever reasons. Visit our project website (here) to learn more!

Bibliography

Bresson, A. 2019. ‘Slaves, Fairs and Fears: Western Greek Sanctuaries as Hubs of Social Interaction.’ In Freitag, K. and M. Haake (eds.) Griechische Heiligtümer als Handlungsorte: zur Multifunktionalität supralokaler Heiligtümer von der frühen Archaik bis in die römische Kaiserzeit. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. 251–277.

Hopkins, K. 1978. Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lepke, A., L. Rubinstein and C. Taylor (eds). In preparation. Women and Manumission in the Ancient Greek World. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Kamen, D. 2023. Greek Slavery. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Lewis, D. 2018. Greek Slave Systems in Their Eastern Mediterranean Context, c. 800-146 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mulliez, D. 2021. ‘Esclaves et affranchis à Delphes : une main-d’œuvre indifférenciée, mais indispensable’ in Malliot, S. and J. Zurbach (eds) Statuts personnels et main-d’œuvre en Méditerranée hellénistique. Presses universitaires Blaise-Pascal. 141–64,

---- 2017. ‘La loi, la norme et l’usage dans les relations entre maîtres et esclaves à travers la documentation delphique (200 av. J.-C.-100 ap. J.-C.)’ in Esclaves et maîtres dans le monde romain: expressions épigraphiques de leurs relations. Paris: École Française de Rome. 13–30

Sosin, J.D. 2025. ‘Manumission with Paramone: Conditional Freedom?’ TAPA 145.2.

Thomsen, C.A. In press. Stemmer fra antikken Ancient Greek Voices. Frederiksberg: Frydenlund Academic.

Thomsen, C.A., Larsen, K.L. and M. Rechendorff Møller. In press. ‘Patterns of Migration in the Eastern Mediterranean 400 BCE – 100 CE’ in Isayev, E., Jewell, E., et al. (eds) Mobility in Antiquity: Rewriting the Ancient World through Movement. Abbingdon: Routledge.

Vlassopoulos, K. 2021. Historicising Ancient Slavery. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Zanovello, S. 2021. From Slave to Free: a Legal Perspective on Greek Manumission. Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso.

Zelnick-Abramovich, R. 2005. Not Wholly Free. The Concept of Manumission and the Status of Manumitted Slaves in the Ancient World. Leiden: Brill.

Go back to top