A Community Archaeology of Families – A Call for Collaboration

by John Tierney (john@historicgraves.com), Jacinta Kiely and Maurizio Toscano

Community archaeology challenges archaeologists to be relevant, ambitious and accessible. This article outlines our experience in Ireland in community archaeology as part of the Historic Graves Project (www.historicgraves.com), a community-led survey of historic graveyards. We are now looking for partners who may be interested in collaborating with us and local communities elsewhere in Europe.

In the project, we record graveyards, mostly over 100 years old, and within each graveyard we record all inscribed gravestones (including a geolocation) and from each gravestone we register the people listed. The average Historic Graves Project survey attendee is 55-70 years of age and has a lifetime of learning behind them, and our project has benefited considerably as a result.

In the last 8 years, we have worked with over 500 community groups stretching from north Cork in Ireland to Northumberland in England, but the system is global in design. We average one graveyard survey per week and we run funded training programmes approximately 20 weeks of the year, limited only by available funding. The average project takes approximately 18 months of funding applications and communications to setup and we spend about 25% of our time on project development work. Training for an average community group on one site takes two days, and we generally get the graveyard surveyed in that time; i.e. approximately 200 headstones surveyed, photographed and read, and the resulting dataset published online.

We have received funding from a variety of sources including Rural Development Leader funds, Heritage Council grants, as well as from a range of other local authority and government departments. Some groups fund their own projects. In general, we build partnerships where the different partners bring funding, permission or labour whilst we bring technology & experience.

All of this happens because we created a web platform that has been instrumental in adding a very positive dimension to what can be a problematic area of heritage management. Historic graveyards are the highest profile archaeological sites in Ireland, with many community groups attempting clean ups, surveys and conservation works. Community groups mostly cooperate with the heritage organisations tasked with graveyard care (local authorities, the National Monument’s Service and the Heritage Council) but they sometimes choose not to engage with professional advice and guidance with all of the problems that can entail.

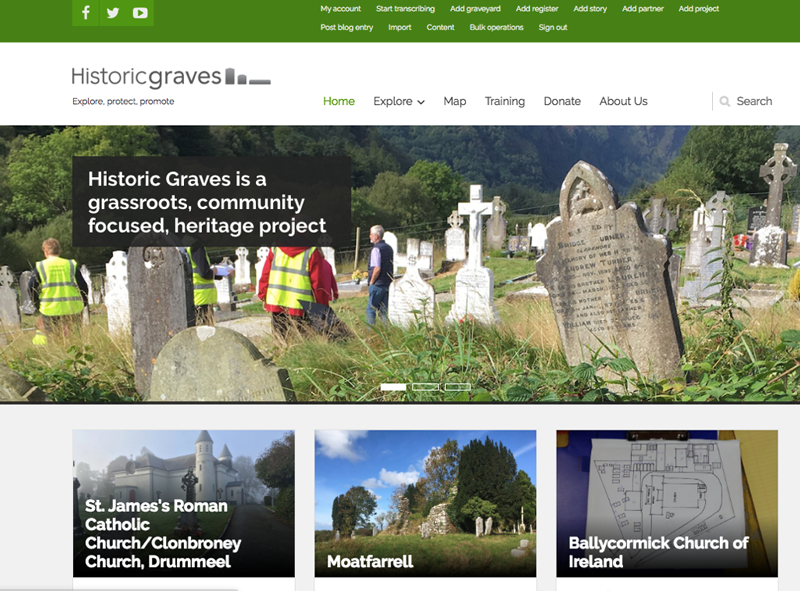

In 2010, I asked my colleague, Maurizio Toscano, to build a web database. Instead, he built the Historic Graves Project web platform (www.historcgraves.com), a complete digital ecosystem for community science with a Drupal based content management system that was updated in 2018 thanks to a Heritage Council grant. In the platform we register graveyards, within each graveyard we register grave memorials, and within each memorial we register people. We now have over a quarter of a million historic names in the database. The platform also allows us to upload multimedia stories, soundscapes, blog posts and local histories written by local participants and us. The web platform can be searched directly, but many of our users use map search to zoom in on area in which they are interested. There are over 800 graveyards online in the system, surveyed and published by over 500 community groups since 2011.

Fig. 1: Screenshot of the Historic Graves web platform (© J. Tierney).

The web platform has just under 1 million page views per year which is small in internet scales but it represents a much broader reach when compared to our company website www.eachtra.ie, where we publish all of our excavation results. The graveyard surveys are based on archaeological survey systems, but the surveys allow people to trace their family headstones to individual graveyards and are therefore of special value for members of the general public interested in their individual family histories, as well as of value for archaeologists, historians and genealogists.

Archaeology has trained us to keep things simple, and that is what we have done with the Historic Graves Project. Even though the project is digital and publishes to our own web platform, paper records are compiled into the individual graveyard folder which is kept by the local survey team. In the graveyard surveys we use record sheets, a sketch sheet (an A4 sheet for a supervisors plan of the graveyard). We maintain a register for record sheets and photography and, after the survey, add a photographic contact sheet. The survey system is the same regardless of whether we are surveying eighty headstones or eight hundred. All of this comprises the simple recording system that it took us about five years to refine.

Working in teams of two people, we first number each gravestone using masking tape and a marker. Because Irish Christian burials are mostly W-E oriented, headstones stand at the west end of the grave and face east. This burial practice, we are told, is designed to face either the rising sun, which is in persona Christi, or to face Jerusalem. In Irish historic graveyards, families purchased and registered individual grave spaces and used graves repeatedly, across multiple generations. Reuse of graves leads to the formation of strong burial rows, albeit often in curving lines and half-rows.

After the numbering, the camera team (a spotter and a photographer) takes one photo per headstone using a camera equipped with a GPS and a daily numbering system. This is a key step in building the web dataset: with one photograph per numbered memorial/monument, the upload of the survey photographs then creates the online records.

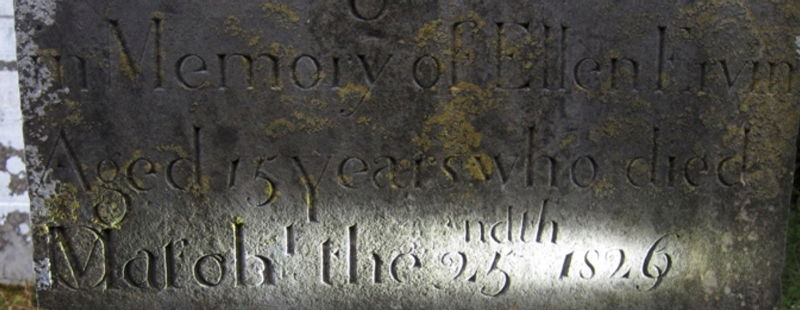

The next step, again in a team of two, is to record the headstone inscriptions. Raking light is our main tool in rapidly reading the inscriptions so we use flash lamps, mirrors and water and a brush. An average headstone takes 10 minutes to read and transcribe and while many of the gravestones are 150-300 years old very few are impossible to read. Phase 1 surveys focus on epitaphs while ornamentation and iconography are covered with more advanced teams.

Fig. 2: Example of headstone inscription under raking light from a flash-lamp (photo: J. Tierney).

By lunchtime of day one, we have taught the community the core survey system. Thereafter it is a matter of heads down and get the work done. A record keeper gathers up the record sheets and collate them every hour or so. We mark an X on the masking tape strip when the headstone is recorded or draw an open box alongside the number if there are unresolved issues. Any gravestones with serious issues unresolved will have a strip of blank masking tape placed on the front face as a clear identifier.

In the afternoon of the first day we then draw the supervisors sketch plan on a single A4 sheet of paper showing the relative location of each numbered gravestone. Optimally, we prefer to have a rectified drone survey done before we visit the site as the accuracy of the survey is greatly improved in this way. However, project funds rarely allow for a drone survey.

The average turnaround from survey to the survey data being live online is 1.5 weeks but we can have a dataset live the next day if circumstances require. If the community takes ownership of the project then they drive the completion of the survey and the online data entry. This is a key point – we archaeologists are partners in the project but the community are responsible for completion. The quickest we have completed a project (from survey to complete online data entry) is 2 weeks and the average is three months from start to finish.

A Community Archaeology of Families

We developed this historic graveyard survey and publication system following the 2008 World Archaeological Congress 6 in University College Dublin. Knowing the development-led side of our business was about to be affected by the global recession, we needed to diversify and we came away from WAC struggling with community archaeology - what it meant and how what we saw in WAC differed from the type of community archaeology projects we had been involved in previously. Essentially, prior to WAC we had been service providers to communities; we were experts providing a service, but the type of community archaeology project shown in the different WAC lectures & workshops were more appealing.

In addition to the influence of WAC 6, our approach to community archaeology changed through what we learned from living in small Irish rural communities. Volunteerism is a strong element of Irish society, and through volunteering with sporting, youth and heritage groups, we developed an approach to projects that was founded on grassroots democracy, devising projects that gave equal benefit to all participants. Also we learned “Don’t worry about the money!” This was advice we were given by sports volunteers who believe that if the idea is a good one then funding and/or support will always be found, and so far, they were right.

How do we get the communities to trust us? We claim no ownership of the data; the local communities do all the work, and we ask that they share it with the local authority and the funding body. This ensures that there are multiple digital versions in multiple locations (as well as our own digital archive system) and in the last few years, we have switched to a creative commons system.

Each community editor can directly download his or her own dataset and the heritage dataset is a key product for us. We are not only creating experiences, or helping to tell stories - we are primarily building community heritage datasets. That is what brings most visitors to our web platform. Communities must build datasets first, then build stories, and then share it.

As an example, one of our most active groups, the RAMS (Rathcoole Active Men’s Group) from south county Dublin are a retired men’s group who after two days training went on to survey 11 local graveyards across a three year period. The retired men would meet every Tuesday and 6-10 of them would spend a morning in an historic graveyard recording the gravestones while others developed computer skills for the data entry.

Fig. 3: Members of the RAMS team from Dublin in action (photo: J. Tierney).

A key part of the evolution of this community archaeology project is that we started an archaeological survey. For us, the project was going to be about studying the headstones - height, width, thickness, inscription, ornamentation, and then interpretations of power and status. However, this standard archaeological approach isn’t what brought the community groups to the project and it isn’t how the project evolved.

What brought the communities to collaborate with our project was that the graveyards are their living heritage. Their ‘people’ are buried in the graveyard and the gravestones are one component of the archaeology of their own families. It took us a while to realise that we were following academic historians in this area. Local historians and family historians abound in Ireland and academic historians have formalised their approaches into what is called the History of Families - combining genealogy, social history and public history. We have brought the strengths of archaeological fieldwork to the study of the History of Families whereby we can follow many family groups via their gravestones, their homes and lands farmed, back to the 17th century and in some cases even further back. Moreover, as emigration has been a key element in European communities, we also aspire to follow the Archaeology of Families to the new communities they formed in distant countries.

A call for collaboration

We are now looking for partners elsewhere in Europe who might be interested in collaborating with their local communities and us. While different burial practices result in different memorialization systems, the common questions of the Archaeology of Families prevail. Where are people buried? How are they memorialized? How are status and power manifest in memorials and monuments and what does that tell us about the broader cultural landscape?

Working with local authorities and a network of heritage officers and county archaeologists, we learned to always be positive in community interactions. As soon as we allow engagement to become negative, we lose our audience and our partners. Therefore, we encourage community groups to put away the pick-axe and shovel and instead take up a camera and a clip board. Our surveys frequently become the first step of a project that ends up with more detailed surveys and development of conservation plans, and even with community groups evolving to engage with other archaeological sites.

Our survey systems have improved over the years because we listened to the community groups and they are still improving for that reason. As part of this project, we stopped being the experts in the room. Very often we are technicians providing training and the communities are the experts in their local heritage, in the local families, local history and the power structures that prevail.

With the Historic Graves project, we identified a problem in Irish heritage and created an archaeological project to address that problem. The problem was our opportunity. That, we believe, is where one future lies for community archaeology in Ireland and Europe. We believe archaeologists can be expert at framing problems and collaborating with communities to build solutions because of our unique spatial and temporal views of the world.

Over the last decade we have spent time working with community groups, local government staff, heritage council staff, fellow archaeologists, historians, genealogists and ecologists. We now see archaeology not as an isolated profession, but as a strong toolset of methods and ideas that can be integral to community engagement for social good. If anybody is interested in building a collaborative project to which they can bring permission, labour, funding or other supports then please feel free to get in touch.

References

https://historicgraves.com/sites/default/files/presentation/index.html#/

Go back to top