by Eleni Chrysafi (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki)

The Rotunda (Hagios Georgios) in Thessaloniki is a unique monument, a priceless cultural treasure and a vivid site of memory, which offers indisputable evidence of the multicultural tradition of Thessaloniki through the centuries.

The Rotunda owes its name to its circular shape: it constitutes a centrally planned, domed building of majestic proportions, which was erected as an individual building within a temenos to the north end of the palatial complex founded at the beginning of the 4th c. AD, between 305 and 311, on the south-east side of Thessaloniki, by Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus, initially Caesar and later, after AD 305, Augustus of the First Roman Tetrarchy. The Rotunda complex was conceived and built as part of a unified plan, which also included the palace of Galerius and the hippodrome. Nevertheless, it belonged to a separate construction project, and was erected in conjunction with the Arch of Galerius (the so-called Kamara), i.e. the triumphal arch erected in honour of Galerius or the Tetrarchy, very close to the eastern part of the city walls (Figs. 53-55). The excavations held by the architect Ernest Hébrard around 1918 demonstrated the axial connection between the Rotunda and the Arch of Galerius through a ceremonial access, which intersected with the central thoroughfare of the city and led to the palace complex.

Fig. 53. The Rotunda and the Arch of Galerius (after: Kiilerich-Torp 2017, p. 9, fig. 4).

Fig. 54. Rotunda, view from the south (photo E. Chrysafi).

Fig. 55. Rotunda, view from the east (photo E. Chrysafi).

There is no scholarly consensus regarding

the original function of the Rotunda. Its cylindrical shape and its

morphological connection to the circular mausolea of the 4th c. led

to the theory that the Rotunda was founded by Galerius as part of his palace

complex, with the purpose of serving as his mausoleum. The mausoleum

interpretation was revived by Sl. Curcic, who proposed that the Rotunda was

founded by Constantine the Great, most probably in AD 322-323, in order to

serve as his mausoleum, on the occasion of his initial selection of

Thessaloniki as the new seat of the Empire. However, most probably the Rotunda

was erected as a temple of the official imperial cult, according to the model

of Pantheon in Rome, with which it has parallels in shape and size.

The vast cylindrical building of the Roman

Rotunda (24.5 m in diameter) was covered by a large dome, which rises to a

height of almost 30 m On the ground floor, eight square niches with

semi-cylindrical vaults are opened into the thickness of the walls, 6.3 m wide.

Originally, smaller niches were opened between the large ones, and were

decorated with architraves, pediments, columns and statues, all elements that

originally completed the rest of the luxurious decoration of the interior with

marbles and opus sectile. The main entrance was formed in the southern niche,

where led the processional way connecting the Rotunda with the Arch of Galerius

and the palace complex.

After the recognition of Christianity as

the official state religion in AD 391, the pagan temple of the Roman Rotunda

was converted into a Christian church sometime between the end of the 4th

c. and the 6th c. The reasons for this conversion remain uncertain,

as does the exact date. When the Roman building was turned into a church, some

alterations and additions related to the Christian use were made. The most

important of these alterations were: a) the mosaic decoration of the dome, the

eight niches in the ground floor and the nine lunettes at the base of the drum,

b) the addition of the semi-circular apse and the vault of the holy bema to the

east side, c) the addition of a continuous ambulatory around the Roman core,

element which was eliminated in later times.

Probably, the various Christian

interventions and alterations are dated from different times. In order to

create the sanctuary area, the eastern ground niche was pierced and enlarged,

as well as a part of the eastern wall around it. This intervention disturbed

the static equilibrium of the Roman building. Consequently, after a powerful

earthquake, the upper part of the dome collapsed. After its reconstruction, it

was decorated with a high-quality mosaic composition. Later than the

restoration of the dome and its mosaic decoration, in the course of a second

reconstruction of the Christian church, most probably during the Early

Byzantine period, are to be dated the following alterations and interventions:

a) the addition of a circular ambulatory as a covered loggia of 8 m width (the

back walls of the seven ground niches were pierced in order to permit the

communication of the ambulatory with the central area of the church), b) the

addition of the holy bema at the east side, c) the addition of a monumental

entrance at the southern niche, consisting of a vestibulum abutting to a

tribelon, which connected the church with the palace complex through a

colonnaded passageway that ended under the Arch of Galerius, d) the addition of

two annexes near the southern monumental entrance, a circular martyrion at the

northern side and an octagonal baptistery at western side. None of these

additions, apart from the sanctuary area to the east, are preserved today.

The large-scale interventions

at the Rotunda severely aggravated the structural integrity of the initial

Roman building. At the beginning of the 9th century, a powerful

earthquake caused some heavy damages, the most important of which was the

collapse of the barrel-vault of the sanctuary, as well as of a part of the

eastern side of the dome. After the restoration of the dome and the sanctuary

area, two flying buttresses were added on either side of the apse, for support.

The semi-dome of the sanctuary was decorated with a wall painting of the

Ascension of Christ, probably in the second half of the 9th century.

This has suffered a lot because it was coated with plaster when the church was

converted into a mosque in 1591.

Fig. 56. Rotunda, mosaic in the southern niche (from: Pazaras 1985, colour pl. II).

Fig. 56. Rotunda, mosaic in the southern niche (from: Pazaras 1985, colour pl. II).

The most important of the alterations made in the Rotunda in connection

with the conversion of the pagan temple into a Christian church, was the

decoration of the dome and other inner surfaces with impressive mosaics,

recognized as masterpieces of the Early Christian and Byzantine mosaic art in

concept, as well as in execution. On the dating of the mosaic decoration of the

Rotunda, different opinions have been proposed, which vary from the late 4th

to the early 6th c. Recently, it has been argued that the dome and

the lunette mosaics are to be dated to the reign of Constantine the Great,

accepting thus the theory that it was this emperor who founded the Rotunda as

his mausoleum.

Fig. 57. Rotunda, mosaic in the south-eastern niche (from: Pazaras 1985, colour pl. I).

Fig. 58. Rotunda, mosaic in the south-eastern niche (from: Pazaros 1985, colour pl. I).

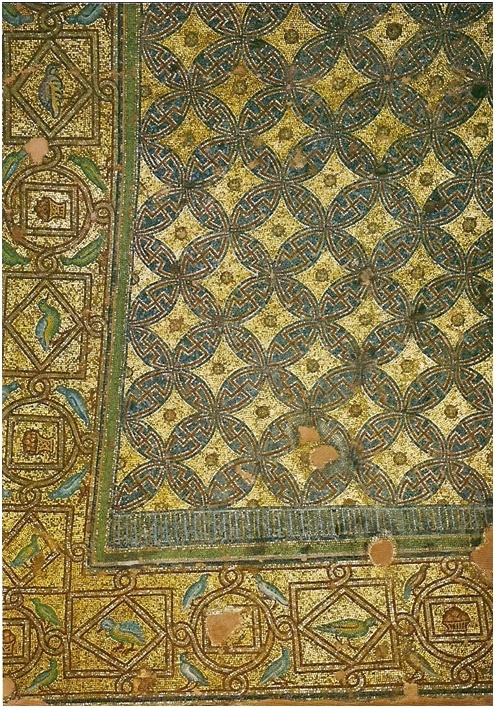

Splendid aniconic mosaics of a purely

decorative character are preserved in the barrel-vaults of three of the ground

floor niches, as well as in the intrados of four of the lunettes at the base of

the drum (Figs. 56-58). All these decorative mosaics are distinguished by

originality, refinement, richness in colour and a naturalistic rendering on

gold or silver ground. They use a variety of themes and motifs, following

patterns already well established in the iconographic repertory of the Roman

art, which continued to be used mostly in the decoration of the Early Christian

floor mosaics and, to a lesser degree, in the wall-paintings of the same period,

mostly in Rome, Ravenna and Thessaloniki.

Fig. 59. Rotunda, mosaic of the dome, south-western panel (from: Pazaras 1985, pl. 12).

Fig. 59. Rotunda, mosaic of the dome, south-western panel (from: Pazaras 1985, pl. 12).

Fig. 60. Rotunda, mosaics of the dome, north-eastern panel (from: Pazaras 1985, pl. 16).

Fig. 60. Rotunda, mosaics of the dome, north-eastern panel (from: Pazaras 1985, pl. 16).

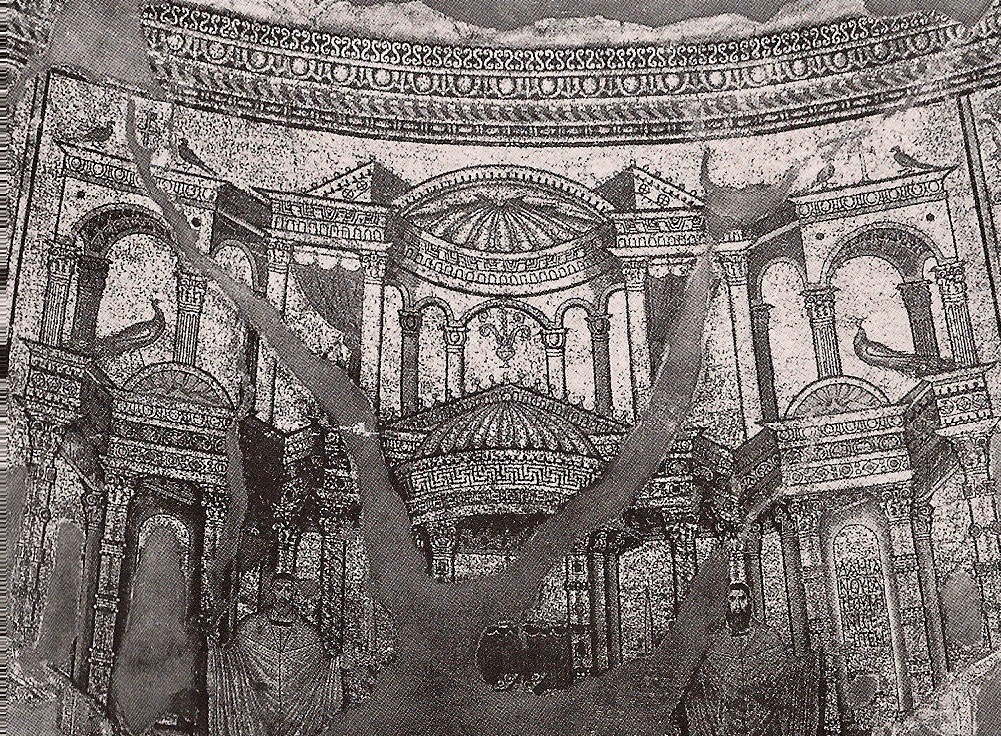

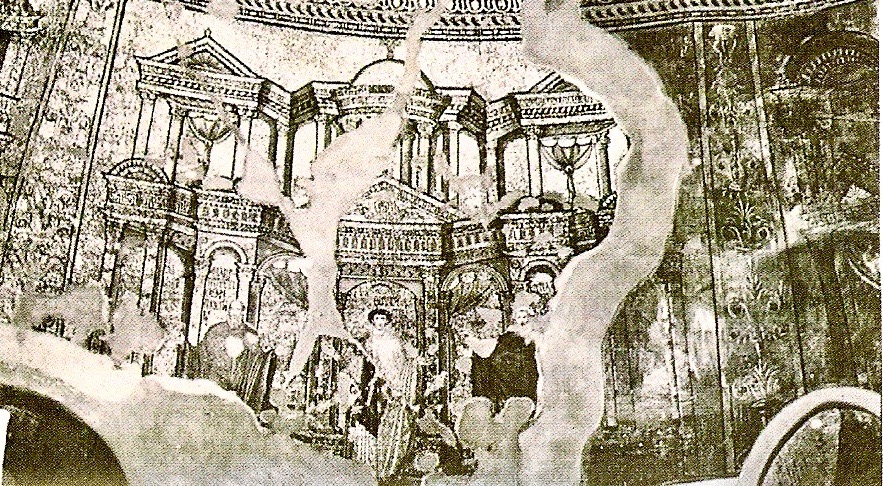

The dome mosaics (Figs. 59-62) extend in three successive concentric zones. The lowest zone of the mosaic decoration, known as the martyrs’ zone, is divided into eight panels by vegetal candelabra. In each panel, orant figures, in groups of two or three, stand in front of complicated architectural compositions of impressive luxury. The name, the profession and the month are reported in the inscriptions that accompany each orant figure. It has been suggested that the twenty standing figures of orants in the mosaics of the Rotunda can be identified with martyrs or donors or members of the imperial court. The eastern panel had been lost already in Byzantine times, after the collapse of the eastern part of the dome, but it was restored in 1889 with the addition of an oil painting, executed by the Italian painter S. Rossi. In the second decorative zone of the dome mosaics, which is for the most part lost today, except for a small part at its bottom, we can only see a greenish ground with a few pairs of sandaled feet and occasionally hems of long white garments. These elements seem to belong to a group of moving male figures identified with saints, prophets or, most probably, angels in a glorifying movement. In the third and upper decorative zone at the dome apex, which is partially preserved, the central medallion is encircled by three bands, a strip of 28 starred rosettes, a rich vegetation garland and a rainbow ring. Inside the central medallion, stood a figure of Christ, now mostly lost but possible to reconstruct according to the tracing preserved on the bricks. The cosmic medallion is supported by four flying angels, whose heads and wings are only partially preserved. Among the angels, east of Christ’s head, there is a representation of Phoenix, the mythical fire-bird, symbol of eternity and rebirth.

Fig. 61. Interior view of the Rotunda (after: Kiilerich-Torp 2017, p. 9, fig. 4).

Fig. 61. Interior view of the Rotunda (after: Kiilerich-Torp 2017, p. 9, fig. 4).

Fig. 62. Rotunda, mosaics of the dome, central medaillon (after Pazaras 1985, colour pl. VIII).

Despite its partial conservation, the mosaic decoration of the Rotunda preserves an original representation of the Heavenly World, a unique synthesis in Early Christian and Byzantine art. The theme of the dome mosaic composition visualizes the triumphal appearance (adventus) of Christ as King of Heaven. Starting from the lower architectural zone of the martyrs, which is a representation of the Heavenly Jerusalem, we pass to the next zone of the Heavenly Court with the Angelic Powers, to end in the theophany of Christ as Heavenly King at the dome apex. The whole mosaic decoration of the Rotunda, full of imperial court connotations, is of an extremely high quality in conception, as well as in execution. The original mosaic composition of the dome represents the earliest known attempt of the Early Christian artists to cover such a large surface with a single unified iconographic program. The extremely symbolic, triumphal, hierarchical and cosmological character of the composition is to be related to a sponsor with a highly developed Christian theological education.

It is highly probable that the Rotunda, in its final form, was used as the church of the palace, a theory implied by different elements. It is obvious that the unique iconographic theme of the dome mosaics was inspired by imperial court ceremony, with emphasis on the hierarchical structure of the different triumphal elements of the palatial decoration. In addition, the Rotunda belonged to the imperial property and was linked to the palace complex through a monumental access with the Arch of Galerius as an intermediate station. Most probably, the rebuilding and mosaic decoration of the Rotunda should be connected with the imperial family and, in particular, with an important event (imperial engagement/marriage etc.) which was planned to take place in Thessaloniki and, in particular, in the palatial church of the Rotunda, which was restored in order to host it.

In the Byzantine period the area around the Rotunda was known as the neighbourhood of the Incorporeal Saints (Asomatoi), while the nearby gateway of the eastern wall was called Gate of the Asomatoi. To these names is related the prevalent opinion regarding the connection of the Christian church with the name Church of the Asomatoi (Incorporeal) or of the Archangels. This name is reported in the written sources and it is to be attributed to the dedication of the Christian church to the heavenly incorporeal powers of the Archangels. The later name Rotunda is related to the circular shape of the monument and it can be found in the texts of the travellers who visited Thessaloniki during the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as in the modern bibliography.

Fig. 63. Rotunda, fragment of the ambo, photo by W. S. George, 1907-1909/10 (BRF; British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

Fig. 63. Rotunda, fragment of the ambo, photo by W. S. George, 1907-1909/10 (BRF; British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

Between 1525 and 1591, the Rotunda became the cathedral of Thessaloniki. After 1591, when the church was converted into a mosque by the sheikh Hortaci Suleyman, it became known as Eski Metropol (Old Cathedral) ή Hortac Efendi Camii. In order to serve the needs of Muslim worship, a minaret and a fountain were added and they are preserved until today. While the Rotunda was a mosque, all of the sacred utensils of the Christian church were transported to the nearby chapel of St George, from which the monument got its later name Hagios Georgios. The church was returned to Christian worship after the liberation of Thessaloniki from Turkish rule in 1912.

Fig. 64. Rotunda, fragment of the ambo,

phot. by W.S. George, 1907-1909/10 (British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

Fig. 64. Rotunda, fragment of the ambo,

phot. by W.S. George, 1907-1909/10 (British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

At the beginning of the 20th

century, the two large sections of the Rotunda ambo (Figs. 63-64), the only

ones preserved, were transported in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul,

where they are exhibited today. In 1918, the marble base of the ambo was

discovered in the centre of a rectangular hall, before the church south porch,

where it can still be seen. According to its reconstruction proposal, the ambo

belongs to the category of ambos in the shape of an open fan. It has also been

proposed that the ambo was originally covered by a circular canopy, which, in

turn, was supported by four slender columns. The furniture was accessed at the

back by means of two sets of steps. Around the lower part of the ambo exterior

there are scalloped niches, each of which is decorated with a figure in high

relief. The whole scene represented the Adoration of the Magi, a unique example

in the decoration of the ambos of the early Christian period. The niches were

separated from each other by Corinthian columns. The whole was crowned all

around by a convex intricate frieze, decorated with a band of saw-toothed

leaves, which ended in a lesbian cornice. On the dating of the Rotunda ambo,

which is considered as a masterpiece of sculpture, given its rare decorative

composition and the delicate sculpture work, different proposals have been put

forward, from the end of the 4th century to the middle of the 6th

century.

Fig. 65. Rotunda, view from the east,

phot. by W.S. George, 1907-1909/10 (British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

Fig. 66. Rotunda, view of the interior looking east, photo by R. Weir Schultz and S. H. Barnsley, 1880-1890 (British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

Fig. 67. Rotunda, view from the south-east, photo by R. Weir Schultz and S.H. Barnsley, 1880-1890 (British School at Athens/BRF Archive).

After the earthquake that afflicted Thessaloniki in 1978, many monuments of the city, among which the Rotunda, suffered some heavy damages. The work of restoration and preservation of the monument lasted for decades because of the impeding large-scale interventions in the building and its mosaic decoration. Consequently, the scaffolds set up in the inner surfaces, in order to facilitate the work of the conservators, covered large parts of the splendid mosaics for almost four decades. When the scaffolding was removed in December 2015, the unique and high-quality mosaic decoration of the dome appeared again in all its splendour and beauty. After the completion of the restoration of the building and its interior decoration at the end of 2015, the Rotunda is open to the public every day and offers to everyone the possibility to visit a unique and emblematic monument related to the multicultural history of Thessaloniki (Figs. 65-67) through seventeen centuries, from the late antique period to today. Erected at a crucial historical point, the Rotunda became the symbol of the end of the Roman world and the transition from paganism to Christianity. Since 1988, the Rotunda is one of the fifteen monuments of Thessaloniki included in the UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage Monument List.

Bibliography (selection)

-

Ch. BAKIRTZIS, E. KOURKOUTIDOU-NIKOLAIDOU, Rotunda, in: Ch. Bakirtzis, E. Kourkoutidou-Nikolaidou, Ch. Mavropoulou-Tsioumi, Mosaics of Thessaloniki, 4th-14th Century, Athens 2012, p. 48-127.

- P. CATTANI, La Rotonda e i mosaici di San Giorgio a Salonicco, Bologna 1972.

- E. CHRYSAFI, Rotunda (Hagios Georgios), in: Impressions. Byzantine Thessalonike through the photographs and drawings of the British School at Athens (1888-1910), Thessaloniki 2012, p. 46-63.

- A. GRABAR, A propos des mosaïques de la coupole de Saint-Georges à Salonique, Cahiers archéologiques 17 (1967), p. 59-81.

- E. HÉBRARD, Les travaux du Service Archéologique de l’Armée d’Orient à l’arc de triomphe “de Galère” et à l’èglise Saints-Georges à Salonique, BCH 44, p. 5-40.

- B. KIILERICH, Picturing Ideal Beauty: The Saints in the Rotunda at Thessaloniki, Antiquité Tardive 15 (2007), p. 321-336.

- B. KIILERICH, H. TORP, The Rotunda in Thessaloniki and its Mosaics, Athens 2017.

- W. E. KLEINBAUER, The Iconography and the date of the mosaics of the Rotunda of Hagios Georgios, Thessaloniki, Viator 3 (1972), p. 27-108.

- W. E. KLEINBAUER, The Orants in the Mosaic Decoration of the Rotunda at Thessaloniki: Martyr Saints or Donors?, Cahiers archéologiques 30 (1982), p. 25-45.

- A. ΜENTZOS, Reflections on the interpretation and dating of the Rotunda of Thessaloniki, Eγνατία 6 (2001-2002), p. 57-82.

- A. MENTZOS, Reflections on the Architectural History of the Tetrarchic Palace Complex at Thessalonike, in: L. Nasrallah, Ch. Bakirtzis, S. J. Friesen (ed.), From Roman to Early Christian Thessalonike. Studies in Religion and Archaeology (Harvard Theological Studies 64), Cambridge, Massachusetts 2010, p. 333-359.

- T. PAZARAS, The Rotunda of Saint George in Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki 1985.

- J.-P. SODINI, L’ambon de la Rotonde Saint-Georges: remarques sur la typologie et le décor, BCH 100.1 (1976), p. 493-510.

- H. TORP, The date of the conversion of the Rotunda at Thessaloniki into a church, Papers from the Norwegian Institute at Athens I. The first five lectures, Athens 1991, p. 13-28.

- H. TORP, Les mosaïques de la Rotonde de Thessalonique: l’arrière-fond conceptuel des images d’architecture, Cahiers archéologiques 50 (2002), p. 3-20.

- H. TORP, Dogmatic themes in the mosaics of the Rotunda at Thessaloniki, Arte medievale, n. s. I.1 (2002), p. 11-34.

- H. TORP, An Interpretation of the Early Byzantine Martyr Inscriptions in the Mosaics of the Rotunda at Thessaloniki, Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia, vol. XXIV (N.S. 10), Roma 2011, p. 11-43.

- G. VELENIS, Some observations on the original form of the Rotunda of Hagios Georgios, Balkan Studies 15 (1974), p. 298-307.

- M. VICKERS, The Date of the Mosaics of the Rotunda at Thessaloniki, Papers of the British School at Rome, n.s. XXV (1970), p. 183-187.